Westminster Restoration and Renewal: A wider view

Wed. 31 Jan 2018

The Hansard Society has long argued that the Westminster Restoration and Renewal debate lacks any vision. As the Commons debates R&R on 31 January, historians Dr John Crook and Dr David Harrison advance a broader view encompassing the whole of a wider World Heritage Site, to realise its archaeological potential and engage the public in its unique history.

, Former House of Commons Clerk

Dr David Harrison

Dr David Harrison

Former House of Commons Clerk

Dr David Harrison is a retired House of Commons Clerk and historian, whose publications include articles on the medieval history and archaeology of Westminster

, Archaeological Consultant

Dr John Crook

Dr John Crook

Archaeological Consultant

John Crook is an archaeological consultant and buildings historian who has researched and published on various aspects of the medieval Palace of Westminster. He was senior historian of the Medieval Palace of Westminster Research Project (2006-12), based at the University of Reading, whose objectives included recreating the medieval palace from survey, graphical, and archaeological evidence.

Get our latest research, insights and events delivered to your inbox

Share this and support our work

The recorded history of Westminster begins c.959 when St Dunstan founded the Benedictine abbey of Westminster on the site of an earlier church in the area misleadingly known as ‘Thorney Island’. Its endowment included a huge estate still approximately represented by the present City of Westminster. This church was replaced by Edward the Confessor’s great Romanesque abbey which, though incomplete, was consecrated just one week before his death in January 1066. Later that eventful year William the Conqueror was crowned there on Christmas Day, thus establishing Westminster Abbey as the place of Royal coronations. The earliest vestiges of the monastic buildings, some now occupied by Westminster School, date from this period.

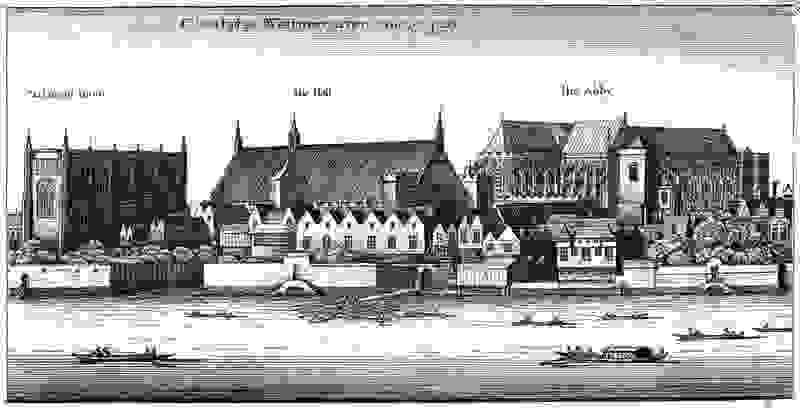

Westminster from the River. Engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar (1647), showing the old Palace of Westminster from NE. Medieval Palace of Westminster Research Project MPW 533.

Most importantly, Edward the Confessor also established a royal palace just east of the abbey buildings: not for nothing is this part of the complex still known as the ‘Palace of Westminster’. Subsequent kings left their mark, with the Great Hall of William Rufus (completed 1099, but with a 1390s rebuilt roof), and Henry II’s Lesser Hall. By this period judges were presiding in the Great Hall. Henry III was the most significant contributor to the complex, initiating the replacement of the fire-damaged abbey church and rebuilding or remodelling much of the palace. Many of his prestigious buildings survived until the early 19th century: the Exchequer, the Painted Chamber (Henry’s ceremonial bed-chamber), and the adjacent Queen’s Chamber and other apartments for Queen Eleanor. To add to the complexity of the site, in 1348 Edward III founded a College of St Stephen, adapting the 1290s palace chapel. The palace was abandoned as a royal residence after another fire in 1512, and Henry VIII moved to Whitehall. Thereafter it continued as the seat of Parliament and Justice: St Stephen’s Chapel became the House of Commons; the Queen’s Chamber and subsequently the Lesser Hall, the House of Lords. The Law Courts continued to sit in the Great Hall.

In the Middle Ages the abbey and palace extended beyond their current boundaries into what is now Parliament Square and surrounding areas. There were gatehouses to the abbey and New Palace Yard, a belfry, streets such King Street (the main road to the north entrance of the abbey) and the ominously-named Thieving Lane and inns such as the Saracen’s Head, all now lost.

Detail from John Norden's Survey (1593), from J. T. Smith, 'Antiquities of Westminster' (1807), additional plate. Medieval Palace of Westminster Research Project MPW 1344.

The demise of the medieval Palace complex in the fire of 1834 is well known, less so the disappearance of the structures in the area around Parliament Square. This was done incrementally as new roads, including Parliament St., George St. and Bridge St., were laid out c.1750 when Westminster Bridge was built. Under Acts of Parliament passed between 1804 and 1814, the warren of narrow streets and small houses were cleared to create an open area which became known as ‘the Desert of Westminster’. Work continued with the construction of the underground through the space and finally Barry’s creation of the present Square in 1866–68.

Main surviving elements of the Palace in 1834, from Chawner & Rhodes survey, superimposed on modern plan. Medieval Palace of Westminster Research Project.

The historic significance of the medieval complex - comprising one of England’s premier abbeys, a college of canons, and a royal palace, the usual meeting place of Parliament and the Courts and the main seat of Government - cannot be over-estimated, though one doubts that its historically integrated nature is apparent to visitors standing in Parliament Square. The Westminster World Heritage Site and Parliament Square, with the Palace, Westminster Abbey, the Supreme Court, and the buildings of Whitehall, are at the heart of the history of the British constitution; but the Square has become a polluted, congested, inaccessible and unwelcoming roundabout. UNESCO has expressed concern about the amount of traffic and pollution, though the boundaries of the World Heritage Site have not yet been extended to include the Square, despite UNESCO’s promptings.

Then-Mayor Ken Livingston sought partial pedestrianisation of the Square, but his plan was dropped under his successor. In 2011 the Hansard Society published ‘A Place for People: A New Vision for Parliament Square’, which pointed out that the surrounding buildings, representing Parliament, Religion, the Judiciary, and Government, made the square the heart of the nation’s constitution and told its history. It argued that with pedestrianisation the square could become a place for public engagement with talks and events, and where people would be informed of the complex history of the constitution and of the buildings in the whole area. Although north and east of the abbey only Westminster Hall and St Mary Undercroft (drastically remodelled) and part of the cloisters survive, there is abundant graphical, survey, and - increasingly - archaeological evidence to allow the lost structures to be reconstructed on paper and by computer modelling.

Reconstruction of the Lesser Hall from NW derived from survey and graphical evidence. Medieval Palace of Westminster Research Project.

Public interest could also be stimulated by a programme of archaeology. There is rich archaeological potential in Victoria Tower Gardens, site of the medieval abbey mill, and future site of the Holocaust Memorial Gardens. Although the construction of the present Houses of Parliament on a thick concrete raft destroyed much archaeological evidence for the eastern part of the site, other areas still have great archaeological potential - as was amply demonstrated during the New Palace Yard works in 1973, when the underground car park was created and the remains of a magnificent medieval fountain found. The site of the Lesser Hall, which remained standing until 1848 while the new palace was going up to the east of it, is under Old Palace Yard. An excavation here would almost certainly reveal the footings of the hall and, deeper still, possibly Edward the Confessor’s royal palace.

Lessons must be learnt from the mistakes of the past, and the current failure to undertake a serious archaeological investigation while the roof of Westminster Hall is cleaned and repaired. When it was repaired by Frank Baines in 1914–23, meticulous record drawings both of the roof and the associated historic masonry were made, but the roof is still not properly understood and today there are techniques unknown in the 1920s such as tree-ring dating. Full recording would normally be a planning condition of works to any listed building, let alone the finest medieval roof in the world; but to almost all experts’ surprise and despite much discussion, this is not being done. To avoid a similar mistake, before any contract for work on Restoration and Renewal is agreed, an assessment must be made of the archaeological potential of the Palace, and this must mean involving the Government’s expert body, Historic England, at an early stage. A lack of consultation could lead to such simple errors as using Old Palace Yard as a storage depot, making archaeological investigation of the area impossible.

The debate about Restoration and Renewal has so far been narrowly focused on the Victorian Palace, cost, and the pros and cons of the various options for temporarily removing MPs and peers from the estate. But there is an opportunity to take a wider view of the whole of what might be called the wider World Heritage Site, which must involve consulting and giving full weight to the views of all significant parties, including UNESCO and Historic England. The appalling terrorist attack in March 2017 has also meant that the whole site has to be considered and added a security dimension to the already powerful case for pedestrianisation.

The Westminster World Heritage Site and Parliament Square could be one of the world’s greatest public spaces, providing a wonderful, welcoming setting for the public: a place to enjoy and reflect on our history. The creation of a great public space and an examination of the rich archaeological potential of the site need not add to delays, and any costs will be minimal compared with the Restoration and Renewal project. If the country is going to spend billions of pounds on this project, there have to be wide public benefits.

Banner image: Engraving (artist unknown). ‘A view from the River Thames of the Parliament House, Westminster Hall, and the Abby’, c.1725. Medieval Palace of Westminster Research Project MPW 601.

More

Related

Blog / The House of Lords after the pandemic

The House of Lords started using ‘post-pandemic’ procedures in September 2021. In doing so, it has taken a significant step away from the ‘virtual’ and ‘hybrid’ proceedings which were introduced in April 2020 and had become normal practice, but it has not made a simple return to pre-pandemic procedures. Pandemic arrangements seem set to have lasting effects.

Briefings / Restoration and Renewal: why MPs should stick with decant and focus on the long-term legacy

On 20 May 2021 MPs will debate the Restoration and Renewal of the Palace of Westminster, laying down a marker about their future expectations for the project. We set out why MPs should support decant and focus on the long-term legacy.

Blog / Groundhog Day for Restoration and Renewal after the Strategic Review: There is still no alternative

The Strategic Review of the Palace of Westminster Restoration and Renewal programme has been published, after 10 months’ work – but political factors mean that implementation of the programme’s main conclusion, that there will be a ‘full decant’ from the building while work takes place, remains in doubt.

Blog / Reviewing Restoration and Renewal and planning for a post-pandemic Parliament

The Coronavirus pandemic has added to the questions surrounding the nature of the Parliament that should emerge from the Palace of Westminster Restoration and Renewal programme. But, with concerns over the programme's governance and public engagement rising, the report arising from the current review of the programme will not now be published this year.

Blog / How Jersey's legislature has risen to the Covid-19 challenge

Jersey's States Assembly was the first legislature in the Commonwealth to hold a full virtual meeting, with all members able to participate, in order to get around the limitations imposed by the Covid-19 crisis. Mark Egan, Greffier of the States, describes how this was achieved and suggests that some of the States Assembly's Covid-19 innovations may stick.

Blog / How are parliaments responding to the Coronavirus pandemic?

When countries are facing a national health emergency, the work of parliaments is as important as ever: to scrutinise government decisions, to authorise expenditure, to pass legislation. But how are legislatures around the world responding to the challenges posed by the pandemic, and what are the key issues involved in moving to a 'virtual' operation?

Blog / The Parliamentary Buildings (Restoration and Renewal) Act 2019: What next?

The House of Commons' last business before it was controversially prorogued on 9 September was the announcement of Royal Assent to the Parliamentary Buildings (Restoration and Renewal) Act 2019. Just as the UK's parliamentary democracy was being questioned, a significant step forward was taken to safeguard the building that both houses and symbolises it.

Journal / Parliamentary Affairs: special issue on 'Parliamentary work, re-selection and re-election' (vol 71, issue 4, 2018)

This special issue of Parliamentary Affairs brings together comparative research across European legislatures to see how much influence MPs' day-to-day legislative and scrutiny work has on voters when they head to the polls. This issue also includes then-Commons Speaker John Bercow's 2016 Bernard Crick Lecture, 'Designing for Democracy'.

Blog / Westminster Restoration and Renewal: A wider view

The Hansard Society has long argued that the Westminster Restoration and Renewal debate lacks any vision. As the Commons debates R&R on 31 January, historians Dr John Crook and Dr David Harrison advance a broader view encompassing the whole of a wider World Heritage Site, to realise its archaeological potential and engage the public in its unique history.

Events / Future Parliament: Hacking the Legislative Process // Capacity, Scrutiny, Engagement

From finance to healthcare, technology has transformed the way we live, work and play, with innovative solutions to some of the world’s biggest challenges. Can it also have a role in how we make our laws?

Latest

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Budget

In order to raise income, the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its taxation plans. The Budget process is the means by which the House of Commons considers the government’s plans to impose 'charges on the people' and its assessment of the wider state of the economy.

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Estimates Cycle

In order to incur expenditure the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its departmental spending plans. The annual Estimates cycle is the means by which the House of Commons controls the government’s plans for the spending of money raised through taxation.

Data / Coronavirus Statutory Instruments Dashboard

The national effort to tackle the Coronavirus health emergency has resulted in UK ministers being granted some of the broadest legislative powers ever seen in peacetime. This Dashboard highlights key facts and figures about the Statutory Instruments (SIs) being produced using these powers in the Coronavirus Act 2020 and other Acts of Parliament.

Briefings / The Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Bill: four delegated powers that should be amended to improve future accountability to Parliament

The Bill seeks to crack down on ‘dirty money’ and corrupt elites in the UK and is being expedited through Parliament following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This briefing identifies four delegated powers in the Bill that should be amended to ensure future accountability to Parliament.

Articles / Brexit and Beyond: Delegated Legislation

The end of the transition period is likely to expose even more fully the scope of the policy-making that the government can carry out via Statutory Instruments, as it uses its new powers to develop post-Brexit law. However, there are few signs yet of a wish to reform delegated legislation scrutiny, on the part of government or the necessary coalition of MPs.