Financial Scrutiny: the Budget

Fri. 23 Apr 2021

In order to raise income, the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its taxation plans. The Budget process is the means by which the House of Commons considers the government’s plans to impose 'charges on the people' and its assessment of the wider state of the economy.

Get our latest research, insights and events delivered to your inbox

Share this and support our work

The Budget is the government’s annual financial statement setting out its view on the state of the economy and the detailed tax measures which it proposes in order to raise revenue.

Parliament’s scrutiny and authorisation of the government’s taxation plans is fundamental to the political system. Parliament provides the crucial constitutional link between government – and its power to take money from the public and spend it on their behalf – and the public themselves. As the public’s representative body, it is Parliament’s responsibility to hold government to account – between elections – for the money it raises and spends. The Budget process has four key parliamentary stages:

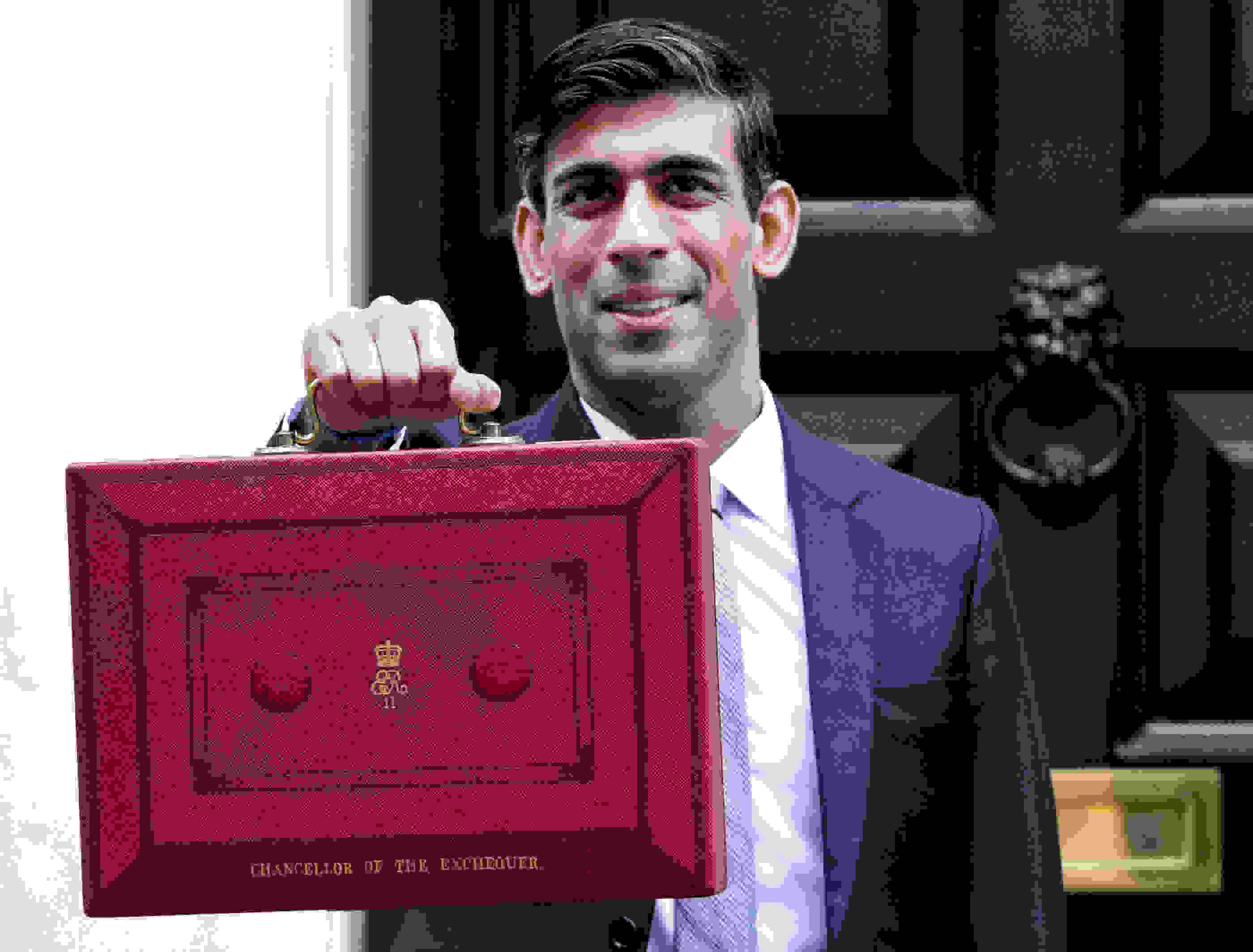

The Chancellor of the Exchequer's statement to the House of Commons consists of two distinct elements: an update on the state of the economy and an outline of the government's taxation plans. The Financial Statement and Budget Report (known as the Red Book) are laid before the House of Commons for scrutiny, accompanied by an array of supporting documentation including economic forecasts from the Office of Budget Responsibility , departmental press notices concerning the tax measures, policy costings, and data sources.

MPs consider the Financial Statement in a wide-ranging debate lasting four days. The debate is organised into topics, with each day dedicated to a particular policy theme or themes (for example, health, education, housing).

Each individual tax or duty must be agreed in the form of ‘Ways and Means’ resolutions. These are put to the House of Commons as motions, which become resolutions once agreed, in the normal way.

Once the Budget resolutions have been agreed, these ‘charging’ or ‘founding’ resolutions form the basis of the Finance Bill. The Finance Bill cannot be introduced until the resolutions are agreed.

Guides / The Finance Bill

The Finance Bill enacts the government's Budget provisions – its income-raising proposals and detailed tax changes. Parliament's scrutiny and authorisation of these taxation plans are crucial in holding the government to account – between elections – for the money it raises and spends.

This Guide covers the first three parliamentary stages of the Budget process. The fourth and final stage, the Finance Bill, is covered in a separate Guide.

The Budget process reflects a number of constitutional principles and procedural rules:

This is the central constitutional principle underpinning the relationship between Parliament and government in relation to both taxation and expenditure. (For these purposes, the Crown is the government.) As Erskine May, the authoritative source on Parliament, sets out, “the Crown requests money, the Commons grant it, and the Lords assent to the grant”. This principle thus precludes Parliament from seeking to impose taxes (‘a charge upon the people’), or authorise expenditure, unless requested to do so by the government.

Control of taxation and expenditure can be exercised only by the House of Commons, not the House of Lords. As Erskine May states, the financial powers of the Upper House are limited ‘by the ancient ‘rights and privileges’ of the House of Commons’ and the terms of the Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949. The role of the House of Lords in respect of finance is ‘to agree, and not to initiate or amend’.

Taxes and duties set out in the Budget are known as a ‘charge upon the people’. Income and corporation tax provisions must be renewed annually in the Budget to maintain parliamentary control over these core revenue streams; but other taxes or duties may be introduced or increased, via the Budget, for a defined period or permanently. The Budget seeks to reconcile spending plans with projected income: the level of revenue requested by the government through taxation should only be that necessary to cover its expenditure (supply) plans.

The government’s taxation plans as set out in the Budget require statutory (that is, legislative) authority. The subsequent Finance Bill provides this.

What is a ‘charge upon the people’?

According to Erskine May, it is

the imposition of taxation, including the increase in rate, or extension in incidence, of existing taxation;

the repeal or reduction of existing alleviations of taxation, such as exemptions or drawbacks;

the delegation of taxing powers; and

the imposition of levies, charges or fees which are akin to taxation in their effect and characteristics.

These are Bills the primary purpose of which is to levy taxes or authorise expenditure. As it is such a Bill, the Finance Bill must:

originate in the House of Commons;

be based on ‘founding’ Ways and Means resolutions; and

adopt particular terminology in both the passage of the Bill and the signification of Royal Assent.

Historically, given the fundamental importance of the Budget, it has been a convention that governments regard the votes at the end of the Budget debate as a matter of confidence. If a vote was lost, it would likely be considered a resigning matter for a government. (Prior to 2011 this would generally have led to a dissolution of Parliament and a general election; however, this is no longer the case due to the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011). MPs – particularly government backbenchers – who vote against their party on the Budget are likely to lose the Whip.

The Financial Statement is followed by usually four days of debate on the Budget in the House of Commons.

The Statement and debate are usually chaired by the principal Deputy Speaker (who is also the Chair of Ways and Means), rather than the Speaker. (There have been occasional exceptions - the Speaker presided in 1968 and 1989.)

The Budget is usually held on a Wednesday, although there is no prohibition on it being held on another day of the week (the Budget of 29 October 2018, for example, was held on a Monday).

If it is held on a Wednesday, the Financial Statement follows Prime Minister’s Questions. On any day, it would follow any Urgent Questions, ministerial statements and Points of Order, should there be any. There are no Ten Minute Rule Bill proceedings on Budget day.

Before the Chancellor of the Exchequer rises to make his speech, a government Whip moves a motion for an ‘unopposed return’, whereby the House requires the production of Budget documents. A motion in the form of a Humble Address to Her Majesty is generally used when the House requests papers from a government department, headed by a Secretary of State. However, the Chancellor is not a Secretary of State and so the motion takes a different form.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer’s speech is then heard without interruption.

Exceptionally, there is no question and answer period following the Chancellor’s Statement. Once the Statement is concluded, two motions are moved formally: a motion for the provisional collection of taxes; and a Ways and Means motion on which the debate will begin.

The Leader of the Opposition is the first speaker called in the debate and is also heard without interruption. The Leader of the third-largest party, who speaks later in the debate, is also heard without interruption when his or her turn comes.

Any former Prime Minister, any former Chancellor of the Exchequer, and the Chair of the Treasury Select Committee and Public Accounts Committee will almost certainly be called to speak early in the debate, if they wish to do so.

In the 2021 Budget debate a call list of speakers has been made available in advance. This procedural change is necessitated by the arrangements for the virtual Parliament during the pandemic.

The budget debate has a theme or themes (health, education, housing, etc) for each day, chosen by the government.

The Shadow Chancellor opens the debate on day two, and a relevant Secretary of State opens the debate on the remaining days, depending on the theme or themes for the day.

There are no winding-up speeches on the first day of debate. A Treasury Minister winds up the debate on the subsequent debate days.

The wide-ranging, topic-based organisation of the budget debate is to enable the House to consider not just the government’s proposals for charges, as set out in the Ways and Means resolutions, but also the role that these charges play in the context of the tax system as a whole, and whether the revenue raised by the proposed charges is sufficient given the government’s expenditure plans and the wider state of the economy.

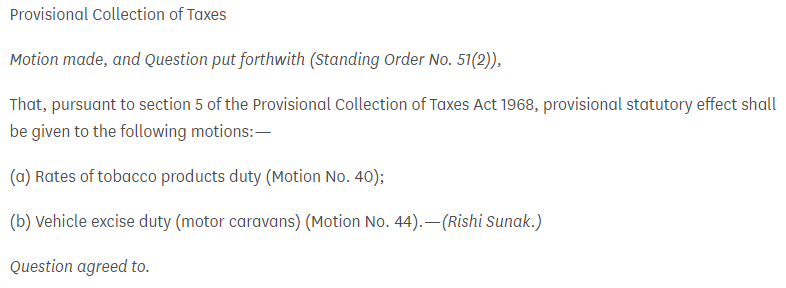

At the end of the Financial Statement, the Chancellor moves two motions:

a Provisional Collection of Taxes motion, to be agreed without debate; and

the first Ways and Means motion. Formally, this is the motion on which the Budget debate takes place.

Why are the Budget resolutions called ‘Ways and Means’ resolutions?

Historically, responsibility for authorisation of taxes lay initially with the Committee of Ways and Means. Resolutions to authorise taxes were thus known as Ways and Means resolutions.

These motions are moved without advance notice of the text being given to the House.

This is contrary to the normal procedure that applies to a motion for debate. Generally, the House of Commons must receive notice of a motion before it can be moved by a Minister. In practice, this usually means that a motion must be tabled at the latest by the close of business on the previous sitting day, so that the text of the motion can appear on the Order Paper for the next sitting day.

However, Standing Order No. 51 exempts Ways and Means motions and Provisional Collection of Taxes motions from this notice requirement. This is to avoid the risks – such as market manipulation or stockpiling of goods – that would arise if people were given advance notice of changes to duties such as those that might be levied on alcohol, fuel and tobacco.

The Finance Act provides the necessary full statutory authority for the changes in taxes and duties that the government proposes in the Budget – but passing an Act of Parliament takes time. Before the Act can be passed, provisional authority must be granted for those changes in taxes and duties that the government proposes should take effect on Budget day or soon after (particularly where market risks attach to any delay).

Provisional authorisation is achieved via a motion under section 1 or section 5 of the Provisional Collection of Taxes Act 1968 (as amended by the Finance Act 2011).

Immediately after the Chancellor’s Statement, MPs are asked to agree, without debate, a single motion providing for changes to pre-existing taxes under section 5 of the Provisional Collection of Taxes Act 1968. This gives provisional statutory effect, as of midnight, to tax changes on certain items detailed in the motion.

If the government, at the end of the four-day debate, chose not to move the motion(s) which are given temporary effect from Budget day by this Provisional Collection of Taxes resolution, or if the motion(s) was rejected by the House, then the validity of the provisional cover for the tax changes would not be immediately affected. However, the House would have to pass the motion(s) within 10 sitting days for it to remain valid.

The suite of Budget motions to be considered at the end of the four-day debate will also include motions tabled under section 1 of the Provisional Collection of Taxes Act 1968 to take effect soon after the conclusion of the debate.

If supported by the House, these too will come into provisional effect pending passage of the Finance Bill. These section 1 Provisional Collection of Taxes motions are identifiable by a declaratory provision in each one that: “..it is declared expedient and in the public interest…”

A Provisional Collection of Taxes resolution remains valid for seven months. However, it is invalidated if the Second Reading of the Finance Bill does not take place within 30 sitting days. (If a Bill other than the Finance Bill is to be used for the purpose of varying the tax, the same rule applies to this alternative Bill.) If the relevant Second Reading failed to take place before the deadline, the government would have to return all taxes raised under the temporary authority provided by the resolution.

The Provisional Collection of Taxes resolution can also be invalidated if: Parliament is dissolved; an Act is passed changing the relevant tax provisions, which supersedes the content of the resolution; or a subsequent motion is passed rejecting the resolution.

Separate Ways and Means resolutions are required to provide parliamentary authority for most tax-raising measures that might be set out in the Budget: to impose a new tax, renew an annual tax, renew a tax with an imminent expiry date, increase the rate of an existing tax, widen the scope of an existing tax, or withdraw or restrict tax relief.

Dozens of Ways and Means resolutions – sometimes as many as 80 or more – may therefore be required to implement a Budget. These ‘founding’ resolutions for the later Finance Bill must be agreed by the House of Commons within 10 sitting days of the Budget statement. They are made publicly available at the end of the Chancellor’s statement.

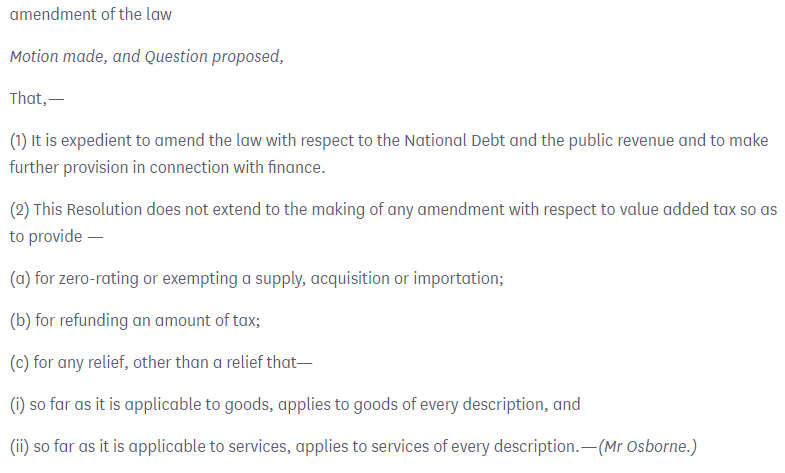

Under Standing Order No. 51, only the first Ways and Means motion is debated and can be amended. This is the motion which is moved by the Chancellor at the end of the Budget statement.

On all the other Ways and Means motions, the question as to whether the House agrees is put ‘forthwith’. That is, there is no debate and the motion cannot be amended. However, the organisation of the budget debate into thematic policy areas, coupled with the latitude typically granted by the Chair, ensures that the debate broadly covers the content of all the motions.

Additional motions related to the Budget, which are not Ways and Means motions, may be moved after the Ways and Means motions are agreed, depending on the government’s requirements. For example a Money motion may be needed to authorise the expenditure of public money.

MPs can propose amendments to only the first Budget (Ways and Means) motion.

Any of the other Budget motions can be divided (voted) upon but they cannot be amended.

This is because under Standing Order No. 51(3) where there is a series of motions the second and subsequent motions have to be put ‘forthwith’ – that is, without amendment or debate.

An amendment to the first Budget motion must be tabled, selected and moved, in order for a vote on an amendment to take place.

The scope for amendment is determined by the scope of the single amendable motion.

Historically, the first Ways and Means motion tabled has often taken the form of an ‘Amendment of the Law’ motion. This usually contains the statement that “it is expedient to amend the law with respect to the National Debt and the public revenue and to make further provision in connection with finance”. Provisions to restrict the scope are usually also incorporated into the motion so the room for MPs to amend it is quite limited. However, this motion does enable the opposition – or indeed government backbenchers – to table amendments setting out alternative tax provisions which can, if selected, then be debated.

If an Amendment of the Law motion is not tabled, then the first Ways and Means motion generally takes the form of a motion for the charging of income tax, as with the motion below from the 2020 Budget.

For an amendment to this motion to be selected it must concern the annual charge on income tax. The scope for amendment is thus very limited.

Historically, an Amendment of the Law motion has not been included among the Budget resolutions shortly after a general election or when the dissolution of Parliament is anticipated (May 1929; February 1974; May 1997; May 2010; June 2017). More recently, the government chose not to table such a motion in 2018 and again in 2020 (shortly after the December 2019 general election).

As well as limiting the scope for debate and amendment of the first Budget motion, the form of the first Budget motion to be moved – that is, whether it is an Amendment of the Law motion or not – also affects the scope for amendment of the subsequent Finance Bill.

For example, an Amendment of the Law motion, if passed, might provide scope for MPs to table amendments to the Bill in areas which may not be covered by the Budget such as tax administration, tax avoidance or tax relief. The absence of an Amendment of the Law motion limits this possibility.

The scope for amendment of the Budget motions and subsequent Finance Bill is also affected by the rules of order for amendments which engage the constitutional principle of the financial initiative of the Crown. This precludes Parliament from seeking to impose taxes (or grant permission for public expenditure) unless requested to do so by the government. MPs who are not Ministers therefore cannot propose their own motions, so they cannot broaden the scope of the subsequent Finance Bill.

MPs cannot increase ‘a charge upon the people’, extend the objects and purposes of a charge, or relax the conditions and qualifications set out by the government when recommending a charge, as this would trespass on the constitutional preserve of the government – its power of financial initiative. MPs can seek only to reduce a tax rate or increase a tax relief, provided that the result of their amendment is not an increase in the charge (compared to the situation prior to their proposed change).

Amendments to the government’s Budget proposals are rare but not unknown. In December 1994, for example, the House supported an amendment to freeze VAT on domestic fuel at 8%, in place of the government’s proposed increase to 17.5%. In March 2016 the government’s proposals were amended to provide for VAT relief on women’s sanitary products.

However, if any of the government’s proposals are amended, then a new Ways and Means motion (or motions) must be introduced to compensate for any lost revenue.

MPs decide on the Ways and Means motions at the end of the Budget debate.

Before MPs decide, the Speaker certifies whether any of the Ways and Means motions are subject to English Votes for English Laws (EVEL). If any of the motions fall within the legislative competence of one or more of the devolved legislatures, then the division on that motion will be subject to double majority voting under the EVEL procedure. (These provisions are temporarily suspended for virtual proceedings in the pandemic-affected Parliament.)

At the end of the fourth and final day of debate on the Budget, the Speaker puts the question on the first Ways and Means motion (that is, the Speaker asks MPs if they agree with the motion). Proceedings take place in the normal way for a decision on a motion:

if the Speaker selects an amendment, the question on the amendment is put first;

if the amendment passes, then the question is put on the motion as amended;

if the amendment does not pass, then the question is put on the original, unamended, motion.

After the first Ways and Means motion has been dealt with, the questions on the remaining such motions are put ‘forthwith’ without further debate.

As there may be dozens of motions, the Chair (usually the Deputy Speaker as Chair of Ways and Means) may take a number of consecutive motions together to save time (for example, “The Question is, that motions 42-55 be agreed to.”).

The House will generally divide (that is, vote) only a few times and only on the most controversial proposals. On 1 November 2018, for example, it divided on three out of 80 motions. (Unusually, on 17 March 2020, by agreement between the parties, there were no divisions on the 63 Ways and Means motions due to Coronavirus-related concerns and a desire to avoid MPs crowding into voting lobbies).

Once the Ways and Means motions are agreed (and thus become resolutions), the government can immediately present the Finance Bill to the House, founded on those resolutions.

Guides / The Finance Bill

The Finance Bill enacts the government's Budget provisions – its income-raising proposals and detailed tax changes. Parliament's scrutiny and authorisation of these taxation plans are crucial in holding the government to account – between elections – for the money it raises and spends.

As is the case for other Bills, the First Reading of the Finance Bill is a formality. The Bill’s long title is read out and a day for its Second Reading is named. This day is often given as ‘tomorrow’. However, this does not mean that the Second Reading will actually take place the following day – ‘tomorrow’ is a procedural device to list the Bill on the Future Business of the House.

In practice, the Second Reading of the Finance Bill may not be held until some weeks after the conclusion of the Budget debate.

Parliament’s consideration of the Finance Bill is covered in a separate Guide.

Following the Budget statement, the Treasury Select Committee in the House of Commons normally conducts a very quick inquiry into the proposals, including by taking oral evidence from experts. The Committee typically aims to publish a report in time for the Second Reading of the Finance Bill.

The House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee may also examine some limited aspects of the Budget proposals and the resulting Finance Bill, if they concern matters such as the administration of the tax system.

Hansard Society Procedural Guide, Financial Scrutiny: The Budget [Available at: https://www.hansardsociety.org.uk/publications/guides/financial-scrutiny-the-budget]

More

Related

Blog / Back to the future? House of Commons scrutiny of EU affairs after Lord Frost's exit

The recent rearrangement of responsibilities for the government’s handling of EU-related affairs raises questions about future parliamentary scrutiny of these issues. In some respects pre-2016 institutional arrangements are restored, but the post-Brexit landscape presents new scrutiny challenges which thus far MPs have not confronted.

Blog / The Health and Social Care Levy Bill: four questions about scrutiny and accountability

The Health and Social Care Levy Bill is being rushed through all its House of Commons stages in just one day on 14 September, only a week after the policy was announced. Before MPs approve the Bill, four important questions about scrutiny and accountability need answering.

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Budget

In order to raise income, the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its taxation plans. The Budget process is the means by which the House of Commons considers the government’s plans to impose 'charges on the people' and its assessment of the wider state of the economy.

Briefings / Who chooses the scrutineer? Why MPs should resist the government's attempt to determine the Liaison Committee chair

Should the Liaison Committee have as its chair someone who is not simultaneously a select committee chair, and should the identity of that person be determined by the government? The answer to these questions will tell us much about how this cohort of MPs, particularly government backbenchers, view the relationship between Parliament and the executive.

Blog / The 2019 Liaison Committee report on the Commons select committee system: broadening the church, integrating with the Chamber

In its recent landmark report, the House of Commons Liaison Committee recommended a widening of the circle of those that select committees should hold to account, and a turn towards the public in all committee activity, but also tighter links between select committees and the House of Commons Chamber.

Blog / The DCMS Committee, Facebook and parliamentary powers and privilege

For its 'fake news' inquiry the House of Commons DCMS Committee has reportedly acquired papers related to a US court case involving Facebook. Andrew Kennon, former Commons Clerk of Committees, says the incident shows how the House's powers to obtain evidence do work, but that it might also weaken the case for Parliament's necessary powers in the long term.

Blog / Contributing to the first full-scale review of Lords scrutiny committees in a quarter-century

Our wide-ranging recommendations to the House of Lords Liaison Committee's review of Lords scrutiny committees, summarised here, aim to improve legislative scrutiny, facilitate more effective horizon-scanning, address post-Brexit scrutiny challenges, and much more.

Reports / Measured or Makeshift? Parliamentary Scrutiny of the European Union

In this 2013 pamphlet, leading politicians, commentators and academics set out growing concerns that parliamentary scrutiny of EU business at Westminster was inadequate, questioned whether there was a democratic deficit at the heart of the UK's relationship with the EU, and canvassed ideas for reform of Parliament's EU engagement.

Reports / Inside the Counting House: A Discussion Paper on Parliamentary Scrutiny of Government Finance

It is widely believed that Parliament’s financial scrutiny work could be carried out more effectively. This discussion paper provides an overview of the current system, describing the processes involved, as well as highlighting its strengths and weaknesses.

Reports / The Challenge for Parliament: Making Government Accountable. The Report of the Hansard Society Commission on Parliamentary Scrutiny

This is the influential 2001 report of the Hansard Society Commission on Parliamentary Scrutiny, chaired by former Leader of the House Lord Newton of Braintree. It urged a step-change in the rigour and importance afforded Parliament's scrutiny work, aimed at putting Parliament at the apex of the system which holds government to account.

Latest

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Budget

In order to raise income, the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its taxation plans. The Budget process is the means by which the House of Commons considers the government’s plans to impose 'charges on the people' and its assessment of the wider state of the economy.

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Estimates Cycle

In order to incur expenditure the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its departmental spending plans. The annual Estimates cycle is the means by which the House of Commons controls the government’s plans for the spending of money raised through taxation.

Data / Coronavirus Statutory Instruments Dashboard

The national effort to tackle the Coronavirus health emergency has resulted in UK ministers being granted some of the broadest legislative powers ever seen in peacetime. This Dashboard highlights key facts and figures about the Statutory Instruments (SIs) being produced using these powers in the Coronavirus Act 2020 and other Acts of Parliament.

Briefings / The Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Bill: four delegated powers that should be amended to improve future accountability to Parliament

The Bill seeks to crack down on ‘dirty money’ and corrupt elites in the UK and is being expedited through Parliament following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This briefing identifies four delegated powers in the Bill that should be amended to ensure future accountability to Parliament.

Articles / Brexit and Beyond: Delegated Legislation

The end of the transition period is likely to expose even more fully the scope of the policy-making that the government can carry out via Statutory Instruments, as it uses its new powers to develop post-Brexit law. However, there are few signs yet of a wish to reform delegated legislation scrutiny, on the part of government or the necessary coalition of MPs.