Controverted elections: how disputed results used to be part and parcel of English political and parliamentary life

Fri. 13 Nov 2020

Disputed parliamentary election results – often taking months to resolve – were a frequent feature of English political culture before the reforms of the 19th century. But how could defeated candidates protest the result of an election, and how were such disputes resolved?

, Newcastle University

Dr James Harris

Dr James Harris

Postdoctoral Research Associate, Eighteenth-Century Political Participation and Electoral Culture, Newcastle University

James Harris is a Research Associate at Newcastle University, and an Associate Fellow at the University of Liverpool. His doctoral research explored political and religious culture in Cornwall and south-west Wales during the later Stuart period. Currently, he is a postdoctoral researcher on the Eighteenth-Century Political Participation and Electoral Culture project (ECPPEC), exploring popular political participation in eighteenth-century elections.

Get our latest research, insights and events delivered to your inbox

Share this and support our work

As I write, Donald Trump still refuses to concede the result of the US presidential election. Although Democrat Joe Biden holds a comfortable lead - in both the electoral college and the popular vote – the Republican incumbent has repeatedly alleged voter fraud and launched legal action in several US states. Such a chaotic election may feel decidedly '2020'. But disputed (or, as historians term them, ‘controverted’) elections – settled over days, weeks and months through legal proceedings – were part and parcel of political life in 18th century England.

In some ways, of course, parliamentary elections in the 18th century were very different from today’s. Polling usually took place not on a single day, but over a week or more. Voting in the Westminster election of 1784 famously lasted for 40 days (putting into perspective the US controversy over how mailed-in ballots have prolonged the election). Before 1872, English electors could not cast their votes in secret, but had to attend the hustings and verbally state their vote. Nor did pre-Reform England enjoy universal enfranchisement. Rather, the right to vote could vary considerably from constituency to constituency, depending on factors including residency, the possession of property, membership of a corporate body, or admission as a freeman – not to mention the fact that voters were universally men.

Although the majority of elections went uncontested (that is, without opposition candidates running), when an opposition did materialise, the result was very likely to be disputed. Perhaps this is unsurprising, given the cost of running a campaign (expensive then, as now), as well as the reputational damage that defeat could cause. Professor Frank O’Gorman’s research has found that between 1715 and 1741 roughly 70% of contested election results were officially challenged. Between 1774 and 1831, it was still around 55%.

Today, allegations of voter fraud hinge on everything from absentee ballots, to deceased voters, to controversy surrounding Sharpie pens. In 18th-century England, defeated candidates could challenge a result on similarly varied grounds. The bewildering array of franchises within constituencies (i.e. the rules which determined who had a legal right to vote) were a fertile source of contention. A frequent complaint was that the returning officer (who presided over the poll and ensured its validity) had been partial in favour of the victorious candidates – for example, he may have been accused of admitting unqualified voters, or pre-emptively closing the poll before all of the electors had been polled. Other common complaints rested on the conduct of the election process: allegations of bribery and corruption were rife (not without reason), and elections were occasionally the sites of full-scale riots.

An 18th-century election could be disputed at several points in the electoral process. During the course of the public polling a particular individual’s right to vote could be challenged by the agents of any candidate, with the exact process varying from place to place. In 1768, more than half of the voters in Northampton were required to present witnesses (local men and women) at the hustings to prove their right to vote. Other constituencies dealt with disputed voters following the conclusion of the poll, as in the 1784 Bedfordshire election. As electioneering become more professionalised over the course of the century, candidates increasingly employed counsel to appear on their behalf at the hustings in order to raise objections against voters.

After a result had been declared, the defeated candidate could immediately demand a ‘scrutiny’ to challenge the legitimacy of the outcome and ‘scrutinise’ the credentials of voters – although these requests were often denied. The practicalities of examining hundreds or even thousands of individual votes before the commencement of the new parliament made scrutinies highly ineffective, and they rarely unseated successful candidates. In the Westminster election of 1784, Charles James Fox was accused of ‘polling all the Roman Catholic hairdressers, cooks, &c.’, and the defeated candidate swiftly demanded a scrutiny. With the returning officer refusing to declare a legitimate victor until he had completed the tortuous process of examining all of Westminster’s c.12,000 voters, the constituency was left unrepresented for more than eight months.

While Republicans in 2020 may hope to rely on the Supreme Court to secure victory, in 18th-century England the ultimate arbitrator of disputed elections was the House of Commons. Each new parliament was accompanied by a flurry of petitions, by far the most common way in which defeated candidates challenged election results. In 1705, 31 petitions were lodged and read at the bar of the House; this rose to a high point of 99 in 1722, before falling away. Although some petitions were heard at the bar, most were referred to the Committee of Privileges and Elections (which was essentially a ‘Committee of the Whole’).

The Committee ostensibly determined petitions on their merits, but its membership reflected the wider balance of power between government and opposition in the House, and it was used for political purposes by the largest party to unseat opposition MPs and elect supporters. As early as 1702 it was described as ‘the most corrupt council in Christendom’. Between 1715 and 1754, 70% of petitions from candidates supportive of the opposition were simply never heard.

It was under the Whig Sir Robert Walpole (often regarded as Britain’s first Prime Minister) that the Committee was used most flagrantly for partisan ends: it was claimed that Walpole could ‘by the very nod of his head’ carry decisions on controverted elections. It was partly this manipulation of the Committee which provoked the downturn in the number of election petitions following the 1727 election, as Tories increasingly viewed the whole process as futile.

Nonetheless, maintaining control of the Committee required careful management. Members were pressured into attending votes by party leaders (or risk being labelled a ‘slinker’), and heated debates could carry on into the small hours of the morning. A particularly fiery exchange over the Cambridgeshire election of 1698 resulted in two MPs from rival parties duelling in St. James’s Square at night – one combatant wounded the other, broke his sword, and promptly returned to the Committee.

In order to maintain control, it was important for the largest party to secure the Chairmanship of the Committee. When the opposition successfully secured the post in 1741, the Members began to cry ‘Huzza!’ and ‘Victory’ – a chant which was heard and repeated by the crowd in the lobby, and subsequently by ‘those in the Court of Requests, the coffee houses and the streets’ (reminiscent, perhaps, of 21st-century citizens chanting ‘Stop the Vote!’ outside voting centres).

Attempts to reform the petitioning process made some progress in 1770, when the Parliamentary Elections Act (10 Geo. III c. 16) – known as the Grenville Act – determined that petitions would be heard before an impartial Select Committee of 15 Members. These committees were responsible for determining complex legal questions relating to election disputes: depending on the allegations, they would preside over the examination and cross-examination of witnesses to bribery or voter fraud, or assess each individual vote challenged by the defeated candidate. This was, however, a slow and expensive process, which many unsuccessful candidates decided not to pursue.

Although the majority of the population were disenfranchised, they could nevertheless find ways to participate in the process of disputing election results. Witnesses travelled to London to present their evidence to Parliament (often at considerable expense to candidates), and records of their testimonies provide a fascinating insight into the role played by figures who are frequently absent from the historical record (often women). These witnesses could use their testimonies as an opportunity to air local grievances, and provided a crucial link between parliamentary and local political cultures.

Outside of the courtroom, a swathe of popular printed texts shared the latest developments from election disputes with the wider public (just as modern controversies are perpetuated by social media). An attentiveness to this wider context of popular political participation can allow us to put the ‘people’ back into politics.

The complex and multifaceted process of challenging election results in the eighteenth century therefore encourages historians to extend the timeframe of ‘an election’ – which began long before the first vote was cast, and was rarely decided when the poll closed. It also makes us extend our understanding of the social depth of elections.

A new project based at Newcastle University in collaboration with the University of Liverpool, Eighteenth-Century Political Participation and Electoral Culture (@ECPPEC_Project), is currently exploring how people participated in the political process, both with and without the vote. Our hope is that this research will continue to shed new light on the vibrant and fascinating history of the electoral disputes of the past, as we continue to encounter unnervingly similar issues in present-day politics.

Chalus Elaine, ‘Gender, Place and Power: Controverted Elections in Late Georgian England’, in James Daybell and Svante Norrhem (eds.), Gender and Political Culture in Early Modern Europe, 1400–1800 (London, 2016), 179–96

Dyndor, Zoe, ‘Widows, Wives and Witnesses: Women and their Involvement in the 1768 Northampton Borough Parliamentary Election’, Parliamentary History, 30 (2011), 309–23

Speck, W. A., ‘“The Most Corrupt Council in Christendom”: Decisions on Controverted Elections, 1702–42,’ in Clyve Jones (ed.), Party and Management in Parliament, 1660–1784 (Leicester, 1984), 107–21

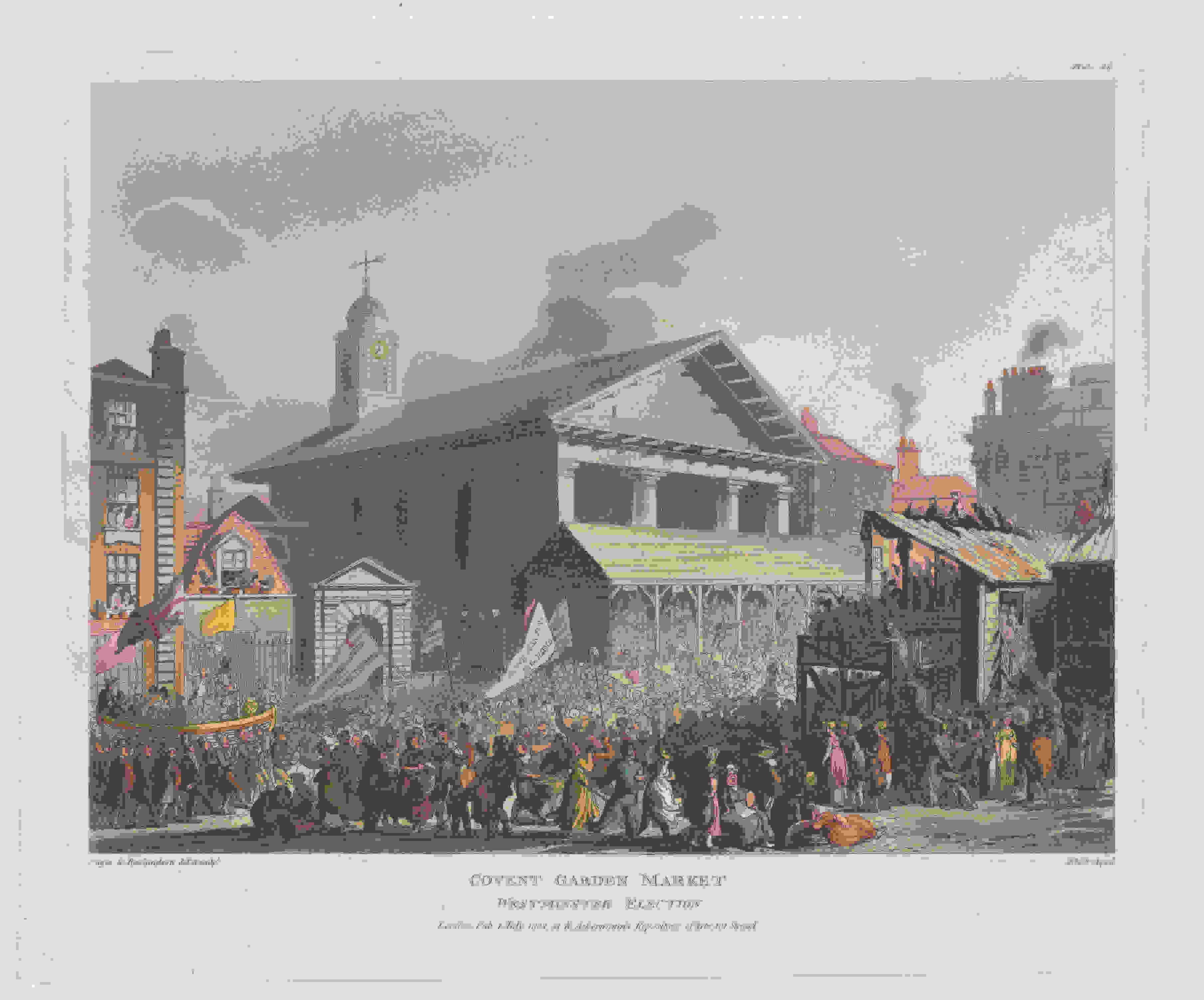

Image Courtesy: Covent Garden Market, Westminster election, 1 July 1808, designed and etched by Thomas Rowlandson and Auguste Charles Pugin. This print records temporary wooden stands erected outside St. Paul's Church in Covent Garden Market to allow politicians running for Parliament in the Westminster election to address voters. On this occasion a large crowd has gathered, carrying banners and spilling out into the square, with some figures perched on a roof at right to listen to a speaker. (Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Creative Commons CCO 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication)

More

Related

Blog / Controverted elections: how disputed results used to be part and parcel of English political and parliamentary life

Disputed parliamentary election results – often taking months to resolve – were a frequent feature of English political culture before the reforms of the 19th century. But how could defeated candidates protest the result of an election, and how were such disputes resolved?

Blog / The Brecon and Radnorshire recall petition process: personal reflections by Sir Paul Silk

As an elector in Brecon and Radnorshire, Hansard Society Trustee Sir Paul Silk sets out 12 shortcomings he observed in the recall petition process that led on 21 June to the triggering of a parliamentary by-election in the constituency.

Journal / Parliamentary Affairs: special issue on 'Parliamentary work, re-selection and re-election' (vol 71, issue 4, 2018)

This special issue of Parliamentary Affairs brings together comparative research across European legislatures to see how much influence MPs' day-to-day legislative and scrutiny work has on voters when they head to the polls. This issue also includes then-Commons Speaker John Bercow's 2016 Bernard Crick Lecture, 'Designing for Democracy'.

Blog / How important are competence and leadership in people's party choice?

At a time of political upheaval – with questions being asked about the leadership, policies and competence of both main UK parties – our Audit of Political Engagement reveals some interesting findings about the ways in which Conservative and Labour supporters view these factors differently and how their importance has changed over time.

Journal / Parliamentary Affairs: special issue on 'The 2017 French presidential and parliamentary elections' (vol 71, issue 3, 2018)

To mark the 2017 French parliamentary and presidential election, this special issue of Parliamentary Affairs looks at the realignment of French politics and revival of the presidency, the demise of the Left, and how policy choices for the Front National influenced its electoral success.

Events / Launch of 'Britain Votes 2017'

On 20 March, Professor Sir John Curtice and a panel of leading commentators outlined their findings at the launch of the first major study of the 2017 general election, 'Britain Votes 2017'.

Blog / The case for more politicians – electoral reform and the Welsh Assembly

The Welsh Assembly’s Expert Panel on Electoral Reform has today re-made the call for an increase in the Assembly’s size. One of the Panel’s members, former Clerk to the National Assembly Sir Paul Silk, here explains why.

Blog / Populist personalities? The Big Five Personality Traits and party choice in the 2015 UK general election

James Dennison examines the association between personality traits and party choice in the 2015 UK General Election.

Blog / Suppose they gave a war and no-one came?

'Suppose they gave a war and no one came?' became a catchphrase of the US peace movement in the 1960s. What happened over the last week in British politics couldn’t help but remind me of it. Why?

Reports / MPs and Politics In Our Time

This 2005 report reviewed the evidence on public attitudes towards MPs and political institutions, and presented findings on MPs' own views of their relationship with voters. It set out a far-reaching agenda for change in the relationship between electorate and the elected in the interests of building public trust and encouraging democratic renewal.

Latest

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Budget

In order to raise income, the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its taxation plans. The Budget process is the means by which the House of Commons considers the government’s plans to impose 'charges on the people' and its assessment of the wider state of the economy.

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Estimates Cycle

In order to incur expenditure the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its departmental spending plans. The annual Estimates cycle is the means by which the House of Commons controls the government’s plans for the spending of money raised through taxation.

Data / Coronavirus Statutory Instruments Dashboard

The national effort to tackle the Coronavirus health emergency has resulted in UK ministers being granted some of the broadest legislative powers ever seen in peacetime. This Dashboard highlights key facts and figures about the Statutory Instruments (SIs) being produced using these powers in the Coronavirus Act 2020 and other Acts of Parliament.

Briefings / The Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Bill: four delegated powers that should be amended to improve future accountability to Parliament

The Bill seeks to crack down on ‘dirty money’ and corrupt elites in the UK and is being expedited through Parliament following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This briefing identifies four delegated powers in the Bill that should be amended to ensure future accountability to Parliament.

Articles / Brexit and Beyond: Delegated Legislation

The end of the transition period is likely to expose even more fully the scope of the policy-making that the government can carry out via Statutory Instruments, as it uses its new powers to develop post-Brexit law. However, there are few signs yet of a wish to reform delegated legislation scrutiny, on the part of government or the necessary coalition of MPs.