What is the Queen's Speech debate and how does it take place?

Fri. 13 Dec 2019

There is a Queen's Speech debate in both Houses, across several days. It provides an occasion for a wide-ranging and constitutionally significant debate on the Government's policies and programme.

Get our latest research, insights and events delivered to your inbox

Share this and support our work

Last updated: 3 May 2022

After the Queen's Speech has been delivered, each House must respond to it. This response takes the form of a 'humble Address' from the House to the Queen, thanking her for the Speech.

What is a humble Address?

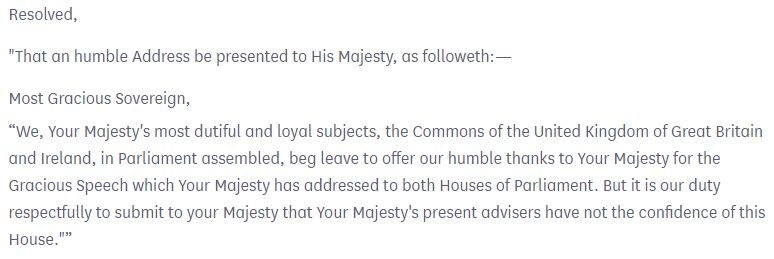

A humble Address is the communication that the House of Commons or House of Lords sends to the Queen when it wishes to address her directly. A motion to make a humble Address must be put before the House and agreed in the normal way, and is amendable.

Each House must formally agree to make the humble Address. It does so by debating and agreeing a motion "That an humble Address be presented to Her Majesty, as follows: ...", with the following words of thanks varying slightly between the Commons and the Lords. The 'Queen's Speech debate' is the debate on this motion. The debate is properly called the 'Debate on the Address' – referring to the Address to be made by the House, not the Speech made by the Queen. (Sometimes, the House's Address is also called the 'Loyal Address'.) The debate ends when the motion to present the humble Address to the Queen is put to the House for a decision, in the normal way.

The motion to present the humble Address is amendable, but it may be amended only to add further text at the end of the original motion.

The debate on the Address allows a wide-ranging debate on virtually any aspect of government policy.

The Queen's Speech debate normally lasts for five or six sitting days in total. In the Commons, in recent years the debate has consistently lasted for six sitting days. The House of Lords' debate is sometimes a day shorter than the Commons'.

The debate on the Address is Government business. The Government thus decides, each time, how many and which parliamentary days to allocate to it. The Government does not need to secure either House's agreement to a business motion in order to schedule the Queen's Speech debate, or to change the schedule which is initially announced.

In both Houses, the Queen's Speech debate normally starts on the day of the Speech.

Normally, the debate takes place on successive sitting days. However, the Government may decide to interrupt the debate at any point after the first day, schedule one or more days on which only non-Queen's Speech business is taken, and then resume the Queen's Speech debate.

Both Houses of Parliament can consider other business during the Queen's Speech debate.

In the House of Commons, it would be normal for the Queen's Speech debate to take priority over other Government business. However, it is possible for the House to take other business in the Chamber as normal while the Queen's Speech debate remains unconcluded, including on days on which the House also debates the Speech. The exception is the first day of the Queen's Speech debate, when there can be no Urgent Questions nor applications for emergency debates under Standing Order No. 24.

The Government determines the day on which the normal daily House of Commons 'question time' of oral questions to Ministers (including Prime Minister's Questions) re-starts. The day on which question time re-starts will be after the day of the Queen's Speech.

There are no sittings in Westminster Hall until after the Queen’s Speech debate in the Commons Chamber is concluded.

In both Houses, the Queen's Speech debate starts with the motion to make a humble Address to the Queen being moved and seconded.

The Queen's Speech debate is the only occasion in the UK Parliament on which a motion is seconded.

In both Houses, the motion is moved by a Government backbencher, not a Minister. The motion is also seconded by a Government backbencher. In both Houses, the two backbenchers are picked by the Government and usually comprise one long-serving Member and one relative newcomer. By tradition, in both Houses the speeches made by the mover and seconder of the motion are unconventional – they do not make controversial political points, and instead may include personal or (in the Commons) constituency-related comments and reminiscences, and they may be humorous.

In the House of Lords, the first day of the debate consists only of the speeches by the mover and seconder of the motion.

In the House of Commons, the speeches by the mover and seconder of the motion are followed, in order, by those of the Leader of the Opposition, the Prime Minister, the leader of the second-largest opposition party, and then other Members.

In both Houses, the first day of the Queen's Speech debate is a general one.

In both Houses, each subsequent day of the debate is normally given a different theme. This is a way of bringing speeches on similar topics together, giving the debate some coherence (and making it easier for Members to decide which day or days to attend). The themes for debate are not necessarily the same in the two Houses.

In the Commons, the subjects of each day of debate are normally announced by the Speaker at the start of the debate.

The House of Lords normally agrees its motion in response to the Queen's Speech without amendment or dissent, and so with no need for a formal decision or vote.

In the House of Commons, there is normally a vote on the motion.

The House of Commons may also decide on amendments tabled to the motion.

Under Standing Order No. 33(1), the Speaker may select up to four amendments for debate and decision. Of these, one may be moved on the penultimate day of debate, and up to three on the final day. Usually, the amendment moved on the penultimate day and one of those moved on the final day are tabled by the Leader of the Opposition.

In the normal way, the House first decides whether it agrees with any of the selected amendments. It then decides whether it agrees with the main motion, in its original form (if no amendments have been agreed) or as amended (if amendment[s] have been agreed).

The motion in response to the Queen's Speech was last amended in 2016, when the Government accepted an amendment tabled by its own backbenchers regretting that the Speech had not included "a bill to protect the National Health Service from the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership".

The Queen's Speech sets out the Government's policies and programme. The House of Commons' vote(s) on the response to the Speech is (or are), in effect, a vote on whether this programme enjoys the support of the House. There has therefore long been a conventional view that votes on the Queen's Speech are in effect a matter of confidence, and that if the Government were defeated it would be obliged to resign or seek an early dissolution of Parliament and General Election.

However, there is no legal requirement to this effect, and the Government has not lost a vote on the Queen's Speech since 1924, so there is a degree of uncertainty around the contemporary position. (During the life of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act [FTPA], 2011-2022, further steps would in any case have been needed to trigger an early General Election.) A Government defeated on the Queen's Speech would certainly be in serious political difficulty.

The obligation on the Government to resign after a defeat on the Queen's Speech would be clearer in either of two possible scenarios:

if the Government stated explicitly before the vote that it was treating it as a matter of confidence; or

if the motion on the Queen's Speech, rather than simply being defeated, were amended so that it explicitly expressed no-confidence. This is what happened in January 1924.

More

Related

Blog / "Will they come when you do call for them?": Should select committees have real power to compel evidence?

In a recent report the House of Commons Privileges Committee recommended the creation of a new criminal offence to deal with the rare problem of recalcitrant select committee witnesses. The proposal is narrow and looks workable. However, it remains controversial, and the Committee has invited further views, with final proposals expected later in 2021.

Guides / What happens on the day of the Queen's Speech and State Opening of Parliament?

The State Opening of Parliament, with the Queen's Speech at its centre, is the largest and most elaborate ceremonial occasion in the regular parliamentary calendar. The ceremony is rich in history and constitutional symbolism, and is also of immediate political interest and importance.

Blog / "... as if the Commissioners had walked into Parliament with a blank sheet of paper": Parliament's procedural handling of the Supreme Court's nullification of prorogation

The Supreme Court's 24 September nullification of the prorogation that had at that point been underway presented Parliament with a procedural and record-keeping problem. Here, the Clerks of the Journals in the two Houses explain how it was resolved.

Blog / The 2019 Liaison Committee report on the Commons select committee system: broadening the church, integrating with the Chamber

In its recent landmark report, the House of Commons Liaison Committee recommended a widening of the circle of those that select committees should hold to account, and a turn towards the public in all committee activity, but also tighter links between select committees and the House of Commons Chamber.

Blog / The Independent Group of MPs: will they have disproportionate influence in the House of Commons?

The roles occupied by members of The Independent Group - particularly on select committees, where they retain a number of important posts and command two and a half times as many seats as the Liberal Democrats – could give them more influence than their small, non-party status might normally be expected to accord them.

Blog / The DCMS Committee, Facebook and parliamentary powers and privilege

For its 'fake news' inquiry the House of Commons DCMS Committee has reportedly acquired papers related to a US court case involving Facebook. Andrew Kennon, former Commons Clerk of Committees, says the incident shows how the House's powers to obtain evidence do work, but that it might also weaken the case for Parliament's necessary powers in the long term.

Publications / Opening up the Usual Channels: next steps for reform of the House of Commons

In a speech to the Hansard Society on 11 October 2017, of which the full text and audio recording are below, the House of Commons Speaker, the Rt Hon John Bercow MP, proposed three key reforms for the House: a House Business Committee; reforms to procedures for Private Members' Bills; and a loosening of the government's exclusive control over recalling the House.

Blog / Corbyn's 'Save Our Steel' e-petition shows why the rules governing the recall of Parliament need to change

In a time of crisis Parliament is hamstrung if it is in recess. MPs are not masters of their own House because, in accordance with House of Commons Standing Order 13, only government ministers - in reality the Prime Minister - can request a recall of Parliament.

Reports / Measured or Makeshift? Parliamentary Scrutiny of the European Union

In this 2013 pamphlet, leading politicians, commentators and academics set out growing concerns that parliamentary scrutiny of EU business at Westminster was inadequate, questioned whether there was a democratic deficit at the heart of the UK's relationship with the EU, and canvassed ideas for reform of Parliament's EU engagement.

Reports / Opening Up The Usual Channels

This 2002 report lays bare the operation of one of the most distinctive, mysterious and critical features of the Westminster Parliament: the 'usual channels' - that is, the relationships between the government and opposition parties through which Parliament's business is organised.

Latest

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Budget

In order to raise income, the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its taxation plans. The Budget process is the means by which the House of Commons considers the government’s plans to impose 'charges on the people' and its assessment of the wider state of the economy.

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Estimates Cycle

In order to incur expenditure the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its departmental spending plans. The annual Estimates cycle is the means by which the House of Commons controls the government’s plans for the spending of money raised through taxation.

Data / Coronavirus Statutory Instruments Dashboard

The national effort to tackle the Coronavirus health emergency has resulted in UK ministers being granted some of the broadest legislative powers ever seen in peacetime. This Dashboard highlights key facts and figures about the Statutory Instruments (SIs) being produced using these powers in the Coronavirus Act 2020 and other Acts of Parliament.

Briefings / The Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Bill: four delegated powers that should be amended to improve future accountability to Parliament

The Bill seeks to crack down on ‘dirty money’ and corrupt elites in the UK and is being expedited through Parliament following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This briefing identifies four delegated powers in the Bill that should be amended to ensure future accountability to Parliament.

Articles / Brexit and Beyond: Delegated Legislation

The end of the transition period is likely to expose even more fully the scope of the policy-making that the government can carry out via Statutory Instruments, as it uses its new powers to develop post-Brexit law. However, there are few signs yet of a wish to reform delegated legislation scrutiny, on the part of government or the necessary coalition of MPs.