Proposals for a 'virtual' Parliament: how should parliamentary procedure and practices adapt during the Coronavirus pandemic?

Tue. 14 Apr 2020

There have been many calls for Parliament to become 'virtual' during the Coronavirus pandemic, using remote working to ensure proper scrutiny of government during the crisis. But how should a 'virtual' Parliament operate?

, Director

Dr Ruth Fox

Dr Ruth Fox

Director , Hansard Society

Ruth is responsible for the strategic direction and performance of the Society and leads its research programme. She has appeared before more than a dozen parliamentary select committees and inquiries, and regularly contributes to a wide range of current affairs programmes on radio and television, commentating on parliamentary process and political reform.

In 2012 she served as adviser to the independent Commission on Political and Democratic Reform in Gibraltar, and in 2013 as an independent member of the Northern Ireland Assembly’s Committee Review Group. Prior to joining the Society in 2008, she was head of research and communications for a Labour MP and Minister and ran his general election campaigns in 2001 and 2005 in a key marginal constituency.

In 2004 she worked for Senator John Kerry’s presidential campaign in the battleground state of Florida. In 1999-2001 she worked as a Client Manager and historical adviser at the Public Record Office (now the National Archives), after being awarded a PhD in political history (on the electoral strategy and philosophy of the Liberal Party 1970-1983) from the University of Leeds, where she also taught Modern European History and Contemporary International Politics.

, The Constitution Unit, University College London

Professor Meg Russell FBA

Professor Meg Russell FBA

Director , The Constitution Unit, University College London

Meg Russell is Professor of British and Comparative Politics and Director of the Constitution Unit. She leads the Unit's research work on parliament, and is currently a Senior Fellow with the ESRC-funded UK in a Changing Europe programme.

Meg has worked closely with policy makers throughout her career. Before joining UCL she had worked in the House of Commons and for the British Labour Party. In 1999 she was a consultant to the Royal Commission on Reform of the House of Lords and from 2001-03 was seconded as a full time adviser to Robin Cook in his role as Leader of the House of Commons. She has acted as an adviser to the Arbuthnott Commission on boundaries and voting systems in Scotland, the House of Lords Appointments Commission, the Select Committee on Reform of the House of Commons ("Wright Committee"), the House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee (PACAC) and the Lord Speaker's Committee on the Size of the House (of Lords). She has regularly given evidence to parliamentary committees, both in Britain and overseas.

Meg sits on the editorial boards of the journals Political Quarterly and Parliamentary Affairs. She is also a former Academic Secretary of the Study of Parliament Group. In 2006 Meg was awarded the Political Studies Association's Richard Rose prize for contribution by a younger scholar to the study of British politics. She was promoted to Reader in 2008 and to Professor in 2014. In 2020 she was elected a Fellow of the British Academy.

Get our latest research, insights and events delivered to your inbox

Share this and support our work

Parliament has an essential role as the guardian of our democracy. But the Coronavirus pandemic poses a huge and unprecedented challenge: how can parliamentarians conduct their core constitutional duties of holding the government to account, assenting to finance, passing legislation, and representing their constituents, when we are all required to adopt rigorous social distancing and, wherever possible, work from home?

At a time when government has been granted emergency powers of a kind unparalleled in peacetime, and ministers are taking rapid decisions that could shape our economy and society for a generation, democratic oversight is vital.

Adversarial party politics take a back seat in a time of national crisis, but Parliament’s collective responsibility to hold the executive to account remains.

As yet, however, there has been little detailed debate about how a ‘virtual' Parliament should operate. Parliament cannot work as normal, so what broad issues must it address in deciding how to work differently?

This post identifies and argues for three core principles:

In the interests of safety, and to set a national example, Parliament should operate as far as possible virtually, rather than accommodating continued physical presence at Westminster.

Parliament should not pursue ‘business as usual’ but should make more radical changes, identifying and prioritising essential business.

Parliament’s crisis arrangements should be based on wide and transparent consultation with Members to maximise support. ‘Sunsetting’ should be used to make clear that they are temporary and create no automatic precedent for the post-crisis era.

In the UK, the government already has much greater control of the way Parliament – particularly the House of Commons – operates than in many other countries. Any crisis arrangements must ensure fair representation for all Members and parties; and the crisis and Parliament’s response to it should not become a pretext to shift power further towards the executive and party managers.

The decisions that Parliament must make in this crisis are unavoidably difficult. But if it demonstrates openness to change, creativity, and willingness to learn and adapt, it will enhance its reputation.

On 6 April the House of Commons Commission confirmed plans to develop a ‘virtual’ House of Commons for MPs’ return from Easter recess on 21 April. This would, through video conference technology, enable MPs to participate remotely in certain parliamentary proceedings, augmenting the remote-working progress already made by select committees. On 7 April the Lord Speaker indicated that similar preparations were underway in the Lords.

But how much of Parliament’s upcoming business should be conducted virtually, and how much, if any, should still take place physically at Westminster?

There could be symbolic benefit in Parliament’s continued functioning at Westminster. But setting an example matters more – in terms of both society’s behaviour and Parliament’s reputation.

The general government guidance, which applies to everybody, is to travel to work ‘only where you cannot work from home’. The travel point is especially pertinent for MPs, many of whom have constituency homes hundreds of miles from Westminster. Similarly on the basis of the government guidance, some Members - particularly in the Lords - should be self-isolating due to their age and health. The Lord Speaker showed leadership at an early stage by announcing his intention to work from home.

Currently, the Commons authorities appear to be planning not for a fully 'virtual' Parliament but for a 'hybrid’ one – that is, where limited numbers of Members (including the Speaker and ministers) come to Westminster as normal to take part in proceedings, in a way that respects social distancing, with others taking part remotely via video conference.

Whatever the model, some staff presence will be required at Westminster to operate the technology. But the risk to public health implied by Members travelling to London, coupled with the need for more staff on site, weighs heavily in favour of all Members avoiding the parliamentary estate. Indeed a joint statement to Peers by the Lords business managers on 9 April accepted that logic for their chamber, arguing that ‘At this difficult time we as Parliamentarians need to play our part and show leadership to the country’.

Critics of a virtual-only Parliament point to the difficulties of having hundreds of Members on video conferences. But, outside key set-piece occasions, chamber attendance rarely involves more than 100 MPs or Peers. The Commons Speaker has already suggested the use of speakers’ lists (already used in the Lords), to help manage participation.

Another challenge is the broadcasting of proceedings. But ultimately what matters is accountability, and protecting health. If live broadcast is temporarily compromised, that may be a necessary price to pay – and committees have already experimented with delayed broadcasts and video clips.

In the current crisis, Parliament must balance the risks of allowing non-Coronavirus-related government action to go inadequately scrutinised against those of expending resources on non-essential activity. There are significant resource constraints, on both Members and staff: trade-offs will be unavoidable. Parliamentarians must also consider the extraordinary pressures on ministers and the civil service.

Some legislatures – including those in France, Germany, Norway and Switzerland – have already adopted an explicitly urgent-only business agenda for the coming weeks. Ultimately at Westminster parliamentarians must decide their priorities, but a similar approach seems appropriate.

What business, then, should be considered critical? The Commons Commission’s 6 April statement gave some pointers, highlighting departmental questions, Prime Minister’s Questions, Urgent Questions (UQs) and ministerial statements. But there are other types of business to consider. Meanwhile (as further discussed below) the House of Lords has already put some forms of business on hold until after the Whitsun recess.

Constructive scrutiny of ministers’ wide-ranging day-to-day decisions is essential; it can support better decision-making and help legitimate those which are most difficult. Scrutiny currently occurs largely through journalists’ questions at the daily Downing Street press conference. Parliamentary involvement adds much more: democratic accountability, opposition and backbench voices, and the relaying of constituents’ experiences. Parliamentarians' continued support is essential to maintaining trust and confidence in the government’s pandemic strategy.

Under the normal cycle of Commons departmental questions, MPs will have no guaranteed opportunity to question the Health team until 28 April, and the Treasury team until 12 May. In the current circumstances, this is inadequate. In the Lords, where daily questions are to the whole government frontbench, there is greater flexibility.

At present, Urgent Questions (UQs) are the best way for MPs to question ministers on pressing issues. But rather than allowing as much as 45 minutes for each urgent question (as normally), 30-60 minutes each sitting day could be guaranteed for short exchanges on 3-4 questions. This would not require Standing Order change, as the timing and choice of UQs is at the Speaker’s discretion. UQs are requested and granted at short notice, but considering other pressures on government, notice could perhaps be given a day in advance.

Beyond UQs (or Private Notice Questions (PNQs) in the Lords), the usual schedule of ministerial questions should be retained, as the full range of Whitehall activity needs to be scrutinised. No government department is likely to be untouched by the Coronavirus crisis. At present, each Commons departmental questions session is dedicated largely to questions tabled in advance, with topical questions permitted only in the last 15 minutes. Given the fast-moving nature of events, the Commons might wish to extend the time for topical questions without notice.

Prime Minister’s Questions (PMQs) are a well-attended ‘set piece’ of the parliamentary week. They are partly political theatre, suited to the intimacy of the Commons chamber. But they rarely allow effective scrutiny, not least because MPs cannot ask follow-up questions.

PMQs via video conference will be a very different beast. For a short experimental period, MPs could therefore trial an alternative format, providing for follow-up questions.

An alternative option would be for the Commons Liaison Committee to undertake fortnightly questioning of the Prime Minister in the PMQs slot. This would allow more in-depth questioning, perhaps allowing the Prime Minister to appear alongside other ministers or expert advisers. However, it would disadvantage MPs who do not sit on the Liaison Committee, including opposition party leaders.

Whatever is decided, the Prime Minister – or whoever deputises for him during his recuperation – must commit to appear before the Liaison Committee soon after it is established, and regularly thereafter. Current circumstances warrant more regular appearances than the normal three per year.

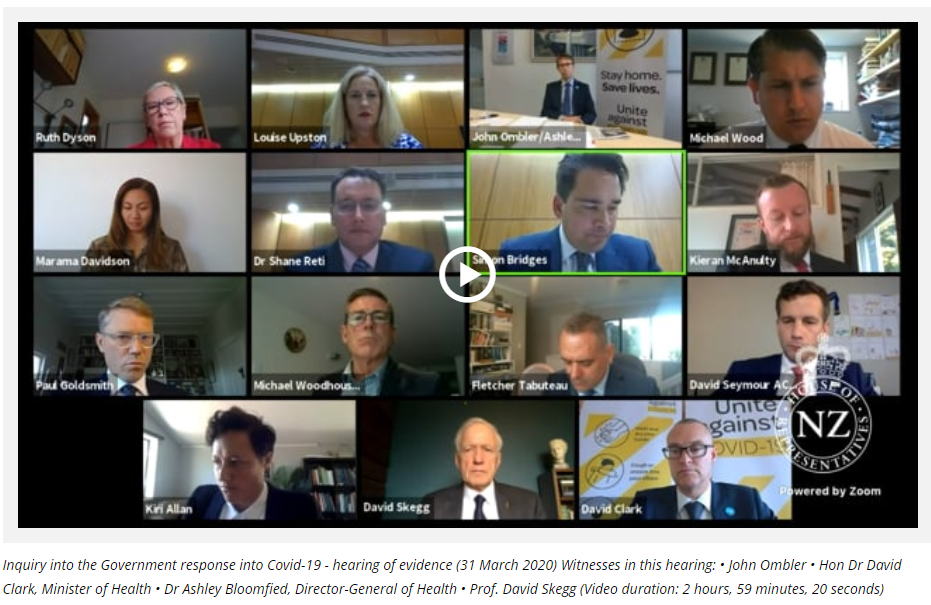

The New Zealand parliament has responded to the pandemic by establishing a new Epidemic Response Committee, made up of senior figures, to oversee the government’s work. Westminster could do something similar.

First remote meeting of the New Zealand Parliament's Epidemic Response Committee on 31 March 2020 (Source: Office of the Clerk/Parliamentary Service. Licensed by the Clerk of the House of Representatives and/or the Parliamentary Corporation on behalf of Parliamentary Service for re-use under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.) {: .caption}

In the short term, adaptation of existing Commons scrutiny mechanisms - including by the Liaison Committee and departmental select committees – may be adequate, but the idea of a dedicated body should be kept under review. The House of Lords can set up temporary special inquiry committees; it has not yet chosen these for 2020-21, so could take up this idea. Establishment of a Lords committee would not require government support, unlike in the Commons.

Even with much business suspended, the government must secure some primary legislation in the coming months. An immediate priority is the Finance Bill, which must have its Second Reading within 30 sitting days of the Budget resolutions (17 March). The other current priority is Brexit-related legislation covering a host of policy areas – which relates to the politically-contentious question of whether the transition period will be extended.

Whatever arrangements are made for parliamentary scrutiny of bills, a principle of fair representation for all Members and parties must be respected.

In the Commons, the committee stage of bills is usually taken in a Public Bill Committee (PBC). Several such committees can operate in parallel, and usually take oral evidence. In the Lords, no more than two bills’ committee stages can be taken simultaneously, and oral evidence is not taken. Given the potential strain on resources, the Commons might similarly limit the number of simultaneous PBCs to two.

Several dozen Statutory Instruments (SIs) subject to the affirmative procedure, including Coronavirus-related regulations, are awaiting debate and approval by both Houses before they can come into or remain in force. More will likely be laid in future weeks. In the Commons, such SIs are almost always referred to a Delegated Legislation Committee (DLC) consisting of up to 17 Members and lasting up to 90 minutes, requiring a clerk, Hansard reporter and broadcasting staff.

In the circumstances, DLCs could be temporarily replaced by a single Grand Committee on Delegated Legislation; the need for the whole House to subsequently approve affirmative SIs would still be retained. This would reduce demand on resources, be more efficient and effective than referring more SIs for full debate in the chamber, and ensure that MPs could focus their scrutiny on the small but critical issues at the heart of an SI.

In the House of Commons, 20 Opposition Days are guaranteed per session, each generating a debate on motion(s) tabled by an opposition party. But ‘debate’ is a challenging concept under either a fully 'virtual' or 'hybrid' solution. In the current climate of constructive engagement rather than point-scoring, opposition parties may not consider the traditional debate-and-division model particularly appropriate. But to deny opposition time altogether would be a retrograde step. An attractive alternative might be shorter and sharper questioning sessions on topics selected by opposition parties, perhaps on a weekly basis.

Voting presents a particular challenge, as highlighted by the former Clerk of the Commons, Sir David Natzler. It has so far been dealt with by avoiding divisions, which is not sustainable longer-term. Some have suggested that Westminster is at a disadvantage in dealing with the pandemic by not having electronic voting as standard, but this is illogical: electronic voting in other parliaments generally takes place in the chamber. Suggestions for some system of ‘pairing’ or proxy voting would also not work readily in an all-virtual environment. What is needed is remote voting by digital means.

This should be possible given the availability of relevant technology. There are many voting apps on the market, although obviously in the parliamentary context security is essential. Options include verification by a unique PIN or registered mobile number.

What is a deferred division?

In the House of Commons, rather than holding each division at the end of a debate (after the 'monent of interruption' - the time when the main business finishes), a division on certain types of business may be deferred to the following Wednesday. On this day MPs may vote on one or more motions, using ballot papers, in the division lobbies. Deferred divisions are particularly used for motions on Statutory Instruments and on unamendable motions.

Synchronous voting is an additional challenge in a remote context; adopting something similar to a ‘deferred division’ model, whereby several votes are taken together at the beginning or end of the day, could ease things considerably. We see no need to contemplate block voting by party whips.

As already noted, the Commons select committees moved early towards remote digital working. The Clerk of the Commons has suggested that after Easter up to 20 remote committee sessions per week could be supported. This indicates no urgent need on technological grounds to scale back the scope of committee inquiries, although flexibility may be required if resources are needed for other essential business or if key staff are incapacitated.

Some other forms of parliamentary proceeding could be temporarily deferred, whether because they do not lend themselves readily to a virtual format or because, during the crisis, the time that they absorb might be better spent on more essential business.

One such example is Private Members’ Bills (PMBs). In the Commons, 13 Friday sittings are set aside for PMBs each session. The rules that apply to PMBs on these Fridays – including closure motions and the quorum – would be difficult to manage virtually, almost certainly requiring Standing Order changes. A commitment from the government to honour the Friday sitting allocation after the crisis could allow MPs to ‘catch up’ later. The speaking slots set aside in the Commons for Ten Minute Rule Bills could also be dispensed with temporarily, to facilitate more time for ministerial questions and statements.

Westminster Hall sittings, where most backbench debates take place, have already been temporarily suspended. Chamber debates determined by the Backbench Business Committee are very important, but a lower priority than other business; again, lost days could be made up later in the session. Likewise, the Commons’ daily 30-minute adjournment debates are a valuable outlet, but suspending all these forms of business on a short-term basis could be justified.

Such changes would bring the Commons into line with the Lords, which agreed as early as 25 March to temporarily suspend Private Members’ Bills and certain non-legislative debates.

A government motion is required for the House of Commons to make any necessary changes to its Standing Orders. No such motion was tabled before the Easter recess, so, for the House to approve it on 21 April, the government would have to move this as a ‘Motion without Notice’. This requires the Speaker’s agreement and, normally, the informal consent of other parties. If there is any risk of a division on this motion, at least 40 MPs must physically return to the Commons after Easter in order to furnish a quorum.

If Members are presented with such a motion as a fait accompli, they may rightly fear being bounced into something that serves the interests of the frontbench rather than the wider interests of Parliament. Those in leadership positions must therefore make maximum efforts to consult with Members in advance, and to maximise the transparency of decision-making.

The response to the pandemic reveals once again the problematic nature of government control of House of Commons procedure.

At a time when wide cross-party agreement is needed, significant power lies with the Leader of the House to determine both the content of the proposals and the style in which they are presented. The Speaker of the House of Commons and other key figures such as the Chair of the Procedure Committee have made suggestions, but it is the executive that in effect makes the decisions. In other parliaments, similar decisions have been facilitated by a wider and more explicitly representative body of parliamentarians – for example, the Conference of Presidents in the French National Assembly, or the Presidium of the Norwegian Storting, both of which are senior cross-party organs focused on organising chamber business. Neither chamber at Westminster has an equivalent (though in the Lords – partly due to its ‘hung’ nature – consultation and more consensual cross-party decision-making is routine).

House of Commons: key dates

21 April: returns from Easter recess

21 May: rises for Whitsun recess

2 June: returns from Whitsun recess

23 June: deadline to extend temporary Standing Order facilitating remote working by select committees

30 June: temporary Standing Order facilitating remote working by select committees expires if it has not been renewed

Another key to achieving buy-in for the new arrangements will be sunset clauses and a clear review process. Just as the Coronavirus Act has a sunset clause and regular review arrangements, so should any parliamentary procedural changes. The temporary Commons Standing Order which facilitates remote working by select committees falls on 30 June unless, by 23 June, the Speaker determines that it should be extended. The same schedule could be adopted for the wider provisions proposed here, ideally with an interim review around the Whitsun recess in late May. If a measure is not working, it should be rectified quickly. And if more adaptations are required, these should be considered quickly. During the interim period, there should be regular reports from the Leader of the House on the operation of the new arrangements, allowing questioning by Members.

Whatever sunsetting and review provisions are put in place, it must be clear that the arrangements made for the crisis are temporary and driven only by the unprecedented situation, creating no automatic precedent for post-crisis times. This is essential to achieve the widespread agreement that is necessary.

After the crisis has ended, a sober analysis can be made of what worked well, what did not, and what procedural adaptations Members might wish to learn from in the longer term.

The authors are grateful for the help and advice that a number of current and former clerks provided during the research for this briefing. In particular, we thank Sir David Natzler, former Clerk of the House of Commons (2015-2018) and currently an Honorary Senior Research Associate at the Constitution Unit, Sir David Beamish, former Clerk of the Parliaments (2011-2017) and currently a trustee of the Hansard Society and an Honorary Senior Research Assoociate at the Constitution Unit, and Paul Evans, former Principal Clerk of Select Committees and a member of the Hansard Society. We would also like to thank Dr Brigid Fowler, Senior Researcher at the Hansard Society, and Lisa James, Research Assistant at the Constitution Unit, for their invaluable assistance.

R. Fox & M. Russell, Proposals for a 'virtual' Parliament: how should parliamentary procedure and practices adapt during the Coronavirus pandemic? (Hansard Society & Constitution Unit, UCL, 2020) [Available at: https://www.hansardsociety.org.uk/publications/briefings/proposals-for-a-virtual-Parliament]

More

Related

Briefings / Who chooses the scrutineer? Why MPs should resist the government's attempt to determine the Liaison Committee chair

Should the Liaison Committee have as its chair someone who is not simultaneously a select committee chair, and should the identity of that person be determined by the government? The answer to these questions will tell us much about how this cohort of MPs, particularly government backbenchers, view the relationship between Parliament and the executive.

Guides / Private Members' Bills

Private Members' Bills are bills introduced by MPs and Peers who are not government ministers. They provide backbenchers with an opportunity to address public concerns and to set a policy agenda that is not determined by the executive. But the procedures, often a source of controversy, are different to those that apply for government bills.

Blog / "... as if the Commissioners had walked into Parliament with a blank sheet of paper": Parliament's procedural handling of the Supreme Court's nullification of prorogation

The Supreme Court's 24 September nullification of the prorogation that had at that point been underway presented Parliament with a procedural and record-keeping problem. Here, the Clerks of the Journals in the two Houses explain how it was resolved.

Blog / The DCMS Committee, Facebook and parliamentary powers and privilege

For its 'fake news' inquiry the House of Commons DCMS Committee has reportedly acquired papers related to a US court case involving Facebook. Andrew Kennon, former Commons Clerk of Committees, says the incident shows how the House's powers to obtain evidence do work, but that it might also weaken the case for Parliament's necessary powers in the long term.

Blog / Fitting a transition / implementation period into the process of legislating for Brexit

The prospective post-Brexit implementation / transition period will require amendments to the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill. Some can be made by the promised Withdrawal Agreement and Implementation Bill, but some could be made before the EU (Withdrawal) Bill is passed. This blogpost by Swee Leng Harris summarises her new briefing paper.

Blog / Trade Bill highlights Parliament's weak international treaty role

The Trade Bill raises concerns about delegated powers that also apply to the EU (Withdrawal) Bill, and need to be tackled in a way that is consistent with it. The Trade Bill also highlights flaws in Parliament's role in international agreements. In trade policy, Brexit means UK parliamentarians could have less control than now, whereas they should have more.

Publications / Opening up the Usual Channels: next steps for reform of the House of Commons

In a speech to the Hansard Society on 11 October 2017, of which the full text and audio recording are below, the House of Commons Speaker, the Rt Hon John Bercow MP, proposed three key reforms for the House: a House Business Committee; reforms to procedures for Private Members' Bills; and a loosening of the government's exclusive control over recalling the House.

Blog / 'Bonfire of the quangos' legislation fizzles out

The forthcoming Great Repeal Bill will be the most prominent piece of enabling legislation since the controversial Public Bodies Act 2011.

Blog / "You can look, but don't touch!" Making the legislative process more accessible

Can technology help change the culture and practice of parliamentary politics, particularly around the legislative process?

Events / Future Parliament: Hacking the Legislative Process // Capacity, Scrutiny, Engagement

From finance to healthcare, technology has transformed the way we live, work and play, with innovative solutions to some of the world’s biggest challenges. Can it also have a role in how we make our laws?

Latest

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Budget

In order to raise income, the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its taxation plans. The Budget process is the means by which the House of Commons considers the government’s plans to impose 'charges on the people' and its assessment of the wider state of the economy.

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Estimates Cycle

In order to incur expenditure the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its departmental spending plans. The annual Estimates cycle is the means by which the House of Commons controls the government’s plans for the spending of money raised through taxation.

Data / Coronavirus Statutory Instruments Dashboard

The national effort to tackle the Coronavirus health emergency has resulted in UK ministers being granted some of the broadest legislative powers ever seen in peacetime. This Dashboard highlights key facts and figures about the Statutory Instruments (SIs) being produced using these powers in the Coronavirus Act 2020 and other Acts of Parliament.

Briefings / The Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Bill: four delegated powers that should be amended to improve future accountability to Parliament

The Bill seeks to crack down on ‘dirty money’ and corrupt elites in the UK and is being expedited through Parliament following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This briefing identifies four delegated powers in the Bill that should be amended to ensure future accountability to Parliament.

Articles / Brexit and Beyond: Delegated Legislation

The end of the transition period is likely to expose even more fully the scope of the policy-making that the government can carry out via Statutory Instruments, as it uses its new powers to develop post-Brexit law. However, there are few signs yet of a wish to reform delegated legislation scrutiny, on the part of government or the necessary coalition of MPs.