Russia-Ukraine crisis: how are sanctions Regulations made and how does Parliament scrutinise them?

Tue. 22 Feb 2022

The UK's new Russia sanctions Regulations, being debated by the House of Commons on 22 February 2022 with one day's notice, highlight the use of delegated legislation to introduce sanctions regimes and the challenges posed for parliamentary scrutiny of urgent measures.

, Researcher

Dheemanth Vangimalla

Dheemanth Vangimalla

Researcher

Dheemanth joined the Hansard Society in July 2021 as a Researcher to contribute to the Review of Delegated Legislation. His role also involves supporting the day-to-day delivery of the Society’s legislative monitoring service, the Statutory Instrument Tracker®.

Dheemanth has a diverse professional background that includes experience in both the legal and non-legal sectors. He completed his MBBS degree at the University of East Anglia. He has since attained a Graduate Diploma in Law (GDL) while working full-time as a junior doctor at an NHS hospital trust. He has previously conducted legal research with the hospital’s legal services department. As a research assistant, he has also contributed to a public international law project concerning citizenship and statelessness. Additionally, he has experience conducting scientific and laboratory-based research during his BMedSci degree in Molecular Therapeutics at Queen Mary University of London.

, Director

Dr Ruth Fox

Dr Ruth Fox

Director , Hansard Society

Ruth is responsible for the strategic direction and performance of the Society and leads its research programme. She has appeared before more than a dozen parliamentary select committees and inquiries, and regularly contributes to a wide range of current affairs programmes on radio and television, commentating on parliamentary process and political reform.

In 2012 she served as adviser to the independent Commission on Political and Democratic Reform in Gibraltar, and in 2013 as an independent member of the Northern Ireland Assembly’s Committee Review Group. Prior to joining the Society in 2008, she was head of research and communications for a Labour MP and Minister and ran his general election campaigns in 2001 and 2005 in a key marginal constituency.

In 2004 she worked for Senator John Kerry’s presidential campaign in the battleground state of Florida. In 1999-2001 she worked as a Client Manager and historical adviser at the Public Record Office (now the National Archives), after being awarded a PhD in political history (on the electoral strategy and philosophy of the Liberal Party 1970-1983) from the University of Leeds, where she also taught Modern European History and Contemporary International Politics.

Get our latest research, insights and events delivered to your inbox

Share this and support our work

On 10 February 2022, the government made and laid a Statutory Instrument (SI) on sanctions against Russia that came into force at 5:00pm the same day - the Russia (Sanctions) (EU Exit) (Amendment) Regulations 2022 (SI 2022/No. 123) (‘Russia sanctions SI’). The SI was made using powers in the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 (‘the Sanctions Act’).

On 21 February 2022, the government announced that the Russia sanctions SI would be debated and decided on by the House of Commons today, 22 February. Ahead of today’s debate, this blogpost outlines the legislative process used to deliver the new sanctions Regulations.

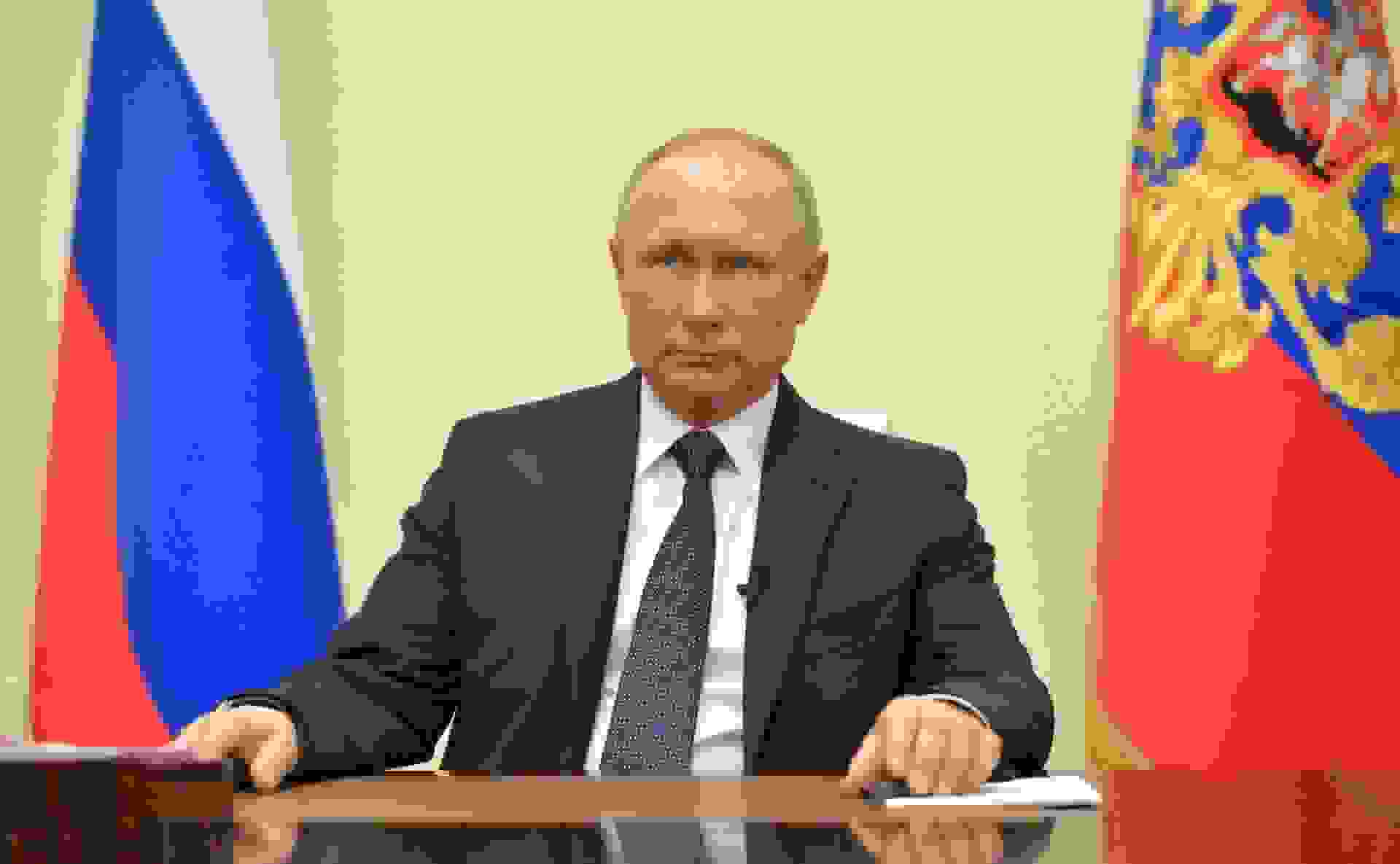

Following Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, the EU introduced sanctions against Russia that had direct effect in the UK. To ensure that the UK continued to operate an effective sanctions regime in relation to Russia after it left the EU, the Russia (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 (SI 2019/No. 855) were made under the 2018 Sanctions Act. These came fully into force at the end of the transition period on 31 December 2020 and replaced the equivalent EU sanctions regimes in UK law. These 2019 Regulations facilitate financial sanctions (including asset freezes), immigration measures, trade sanctions and enforcement powers.

The Russia sanctions SI laid before Parliament on 10 February 2022 amends these 2019 Regulations to broaden the definition of ‘involved person’ who the Secretary of State can ‘designate’ and who would thus become subject to sanctions. The Explanatory Memorandum for the SI explains that expanding the designation criteria will provide a basis for the UK to designate individuals or entities that are or have been involved in obtaining a benefit from, or supporting, the Government of Russia.

When new Regulations are made under the Sanctions Act to amend sanctions Regulations that have already been made under section 1 of that Act, the Minister is required to lay a report under section 46 of that Act stating their reasons for the amendments. The three-point rationale provided in the ‘Section 46 Report’ for the amendment made by the Russia sanctions SI is that:

“designations to be made… will bring coercive pressure to bear against the Government of Russia to encourage it to cease actions destabilising Ukraine, and undermining and threatening its territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence”;

“designations to be made… will constrain the Government of Russia’s ability to maintain its activities with regard to Ukraine. Many of the entities and individuals that could be designated under the amended criteria contribute financially to Russia’s exchequer, or provide resources to the Government of Russia”;

“the amendment itself as well as designations made using it will send a strong signal of condemnation to Russia”.

UK sanctions are implemented primarily through delegated legislation. The main piece of primary legislation which confers power on government Ministers to make sanctions Regulations is the 2018 Sanctions Act.

Other key legislation that might be engaged in making sanctions Regulations - sometimes in conjunction with powers in the Sanctions Act - includes the United Nations Act 1946, the Immigration Act 1971, the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, the Export Control Act 2002, the Counter-Terrorism Act 2008, and the Policing and Crime Act 2017.

Sanctions Regulations may be made to introduce UK-specific measures or measures required by the United Nations Security Council or other international bodies. They often take the form of financial measures such as asset freezes, restrictions on access to financial markets and provision of financial services, directions to cease banking relationships or activities, and anti-money laundering provisions. Measures may also restrict or impose controls on immigration, trade, aircraft and shipping.

The Sanctions Act establishes a legal framework which enables a Minister to impose sanctions to comply with UN and other international obligations, or for other purposes such as the prevention of terrorism, the interests of national security or international peace and security, or the furtherance of a UK foreign policy objective. This is primarily achieved through the delegated powers to make sanctions Regulations which are granted in section 1 of the Act.

Sanctions Regulations under the 2018 Act (made under section 1) are subject to different levels of parliamentary scrutiny depending on what the Regulations relate to:

Regulations are subject to the ‘made affirmative’ procedure if they are ‘non-UN regulations’ and do not repeal, revoke or amend any provision of primary legislation. This means that the Regulations require parliamentary approval but only retrospectively, within a statutory period.

Regulations are subject to the ‘draft affirmative’ procedure if they repeal, revoke or amend any provision of primary legislation. This means that the Regulations require parliamentary approval and cannot be made or come into force until they have received it.

Regulations are subject to the ‘made negative’ procedure if they are not caught by the ‘made affirmative’ or ‘draft affirmative’ criteria. This means that the Regulations do not require active parliamentary approval and can come into force before the end of their 40-day scrutiny period.

Of the 52 SIs laid before Parliament that contain sanctions Regulations made under section 1 of the Sanctions Act, 25 were subject to the ‘made affirmative’ procedure, one the ‘draft affirmative’ procedure, and 26 the ‘made negative’ procedure.

The Russia sanctions SI is subject to the ‘made affirmative’ scrutiny procedure. It is already the law (and has been in force since 5:00pm on 10 February 2022) but needs retrospective parliamentary approval by 19 March 2022 if it is to remain the law. Otherwise, the SI ceases to have effect at the end of that day.

There are problems with arrangements for the parliamentary scrutiny of all affirmative SIs:

Debates are scheduled by the government, often at short notice - in the case of the Russia sanctions SI, at less than 24 hours’ notice.

In the House of Commons, the Government decides whether debates take place in a Delegated Legislation Committee (DLC) or on the Floor of the House.

Debates in the House of Commons normally last for a maximum of only 90 minutes but, on the floor of the House, they can be extended through the agreement of a Business of the House motion - if the Government chooses to move one. In the case of the Russia sanctions SI, the Government has scheduled a Business of the House motion to extend the debate to three hours.

The ‘made affirmative’ procedure also raises concerns about democratic oversight owing to the long delays that can occur between provisions being made into law and them being debated in Parliament. This can happen especially as a result of parliamentary recesses (as was seen with ‘made affirmative’ Covid-19 ‘lockdown’ Regulations in summer 2020). When primary legislation prescribes the ‘made affirmative’ procedure for an SI, it often stipulates that when calculating the scrutiny period “no account is to be taken of any time during which Parliament is dissolved or prorogued or during which both Houses are adjourned for more than 4 days”. Under the Sanctions Act, for example, the default requirement for ‘made affirmative’ SIs is that they must be approved by both Houses before the end of 28 days beginning with the day on which the SI is made. However, the prescribed method of calculating the scrutiny period means that, for a sanctions SI subject to this 28-day scrutiny period, the average time between it being made into law and being debated is 40 and 50 calendar days in the Commons and Lords respectively. (This calculation excludes the Russia sanctions SI).

There has been a proliferation of overly complicated ways of calculating the scrutiny period for ‘made affirmative’ SIs. For example, some Acts specify that only parliamentary sitting days should be used to calculate the scrutiny period, while others have no such specification. Some Acts prescribe a period of 40 days, while others prescribe 28 days. Taking the Sanctions Act as an example, section 55(3) provides for a ‘standard’ ‘made affirmative’ procedure, whereby the SI must be approved by both Houses before the end of 28 days beginning with the day on which the SI is made. However, section 56(5) provides for an alternative process whereby ‘made affirmative’ SIs can instead be subject to a scrutiny period of 60 days beginning with the first day on which any provision of the SI comes into force. There often seems to be no particular rationale for such variation.

Unnecessary inconsistencies increase the likelihood of Government and/or Parliament making timetabling mistakes. Recently, a set of sanctions Regulations ceased to have effect at the end of the 28-day retrospective scrutiny period because government officials and business managers miscalculated the scrutiny period and scheduled the approval debate and vote in the House of Lords after the scrutiny deadline had expired. We uncovered this problem through our monitoring of all SIs laid before Parliament for our SI Tracker, and drew it to the attention of officials in the House of Lords and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. The motion to approve the SI was taken off the Order Paper and the Regulations will now have to be re-made and re-laid before Parliament and approved by both Houses.

As part of our current Delegated Legislation Review, we are giving careful consideration to how the system could best operate in urgent circumstances. Urgent procedures are essential for circumstances which require rapid response by government, as sanctions Regulations show. However, an appropriate balance must be struck between the demands of speedy law-making and parliamentary scrutiny.

Who funds this research?

This research was supported by the Legal Education Foundation as part of the Hansard Society's Delegated Legislation Review.

More

Related

Blog / The care placement Regulations and the courts: too many holes in the net of parliamentary scrutiny?

A forthcoming judicial review on children-in-care highlights parliamentarians' inability to challenge only certain aspects, rather than the whole, of a Statutory Instrument. Courts can and do provide an important backstop against unlawful use of delegated powers, but this does not diminish the need for better parliamentary oversight of delegated legislation.

Blog / Coronavirus Act renewal: Into the sunset?

How does the Coronavirus Act renewal process which is due to take place on 19 October work? How important is the Act in the overall legislative response to the pandemic? And what might MPs take from the process for the delegation of powers in future Acts?

Blog / The Health and Social Care Levy Bill: four questions about scrutiny and accountability

The Health and Social Care Levy Bill is being rushed through all its House of Commons stages in just one day on 14 September, only a week after the policy was announced. Before MPs approve the Bill, four important questions about scrutiny and accountability need answering.

Blog / What is the aim of parliamentary scrutiny of delegated legislation?

Several parliamentary committees scrutinise delegated powers and delegated legislation. But what is the aim of this scrutiny, what standards are applied, and what are the value and limits of Parliament's role in this aspect of the legislative process?

Articles / In the rush to prepare for Brexit, parliamentary scrutiny will suffer

The cancellation of this week's House of Commons recess provided the government with an extra few days to hold debates on affirmative Brexit SIs. But the low number of debates makes it a wasted opportunity. The government can get its Brexit SIs into force by 29 March, but probably only at the expense of what limited scrutiny already takes place for SIs.

Blog / Trade Bill highlights Parliament's weak international treaty role

The Trade Bill raises concerns about delegated powers that also apply to the EU (Withdrawal) Bill, and need to be tackled in a way that is consistent with it. The Trade Bill also highlights flaws in Parliament's role in international agreements. In trade policy, Brexit means UK parliamentarians could have less control than now, whereas they should have more.

Blog / 'Bonfire of the quangos' legislation fizzles out

The forthcoming Great Repeal Bill will be the most prominent piece of enabling legislation since the controversial Public Bodies Act 2011.

Blog / "You can look, but don't touch!" Making the legislative process more accessible

Can technology help change the culture and practice of parliamentary politics, particularly around the legislative process?

Events / Future Parliament: Hacking the Legislative Process // Capacity, Scrutiny, Engagement

From finance to healthcare, technology has transformed the way we live, work and play, with innovative solutions to some of the world’s biggest challenges. Can it also have a role in how we make our laws?

Reports / Measured or Makeshift? Parliamentary Scrutiny of the European Union

In this 2013 pamphlet, leading politicians, commentators and academics set out growing concerns that parliamentary scrutiny of EU business at Westminster was inadequate, questioned whether there was a democratic deficit at the heart of the UK's relationship with the EU, and canvassed ideas for reform of Parliament's EU engagement.

Latest

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Budget

In order to raise income, the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its taxation plans. The Budget process is the means by which the House of Commons considers the government’s plans to impose 'charges on the people' and its assessment of the wider state of the economy.

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Estimates Cycle

In order to incur expenditure the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its departmental spending plans. The annual Estimates cycle is the means by which the House of Commons controls the government’s plans for the spending of money raised through taxation.

Data / Coronavirus Statutory Instruments Dashboard

The national effort to tackle the Coronavirus health emergency has resulted in UK ministers being granted some of the broadest legislative powers ever seen in peacetime. This Dashboard highlights key facts and figures about the Statutory Instruments (SIs) being produced using these powers in the Coronavirus Act 2020 and other Acts of Parliament.

Briefings / The Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Bill: four delegated powers that should be amended to improve future accountability to Parliament

The Bill seeks to crack down on ‘dirty money’ and corrupt elites in the UK and is being expedited through Parliament following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This briefing identifies four delegated powers in the Bill that should be amended to ensure future accountability to Parliament.

Articles / Brexit and Beyond: Delegated Legislation

The end of the transition period is likely to expose even more fully the scope of the policy-making that the government can carry out via Statutory Instruments, as it uses its new powers to develop post-Brexit law. However, there are few signs yet of a wish to reform delegated legislation scrutiny, on the part of government or the necessary coalition of MPs.