Demands to recall the House of Commons over this summer’s exams fiasco reinforce the case for taking the process out of government hands

Tue. 18 Aug 2020

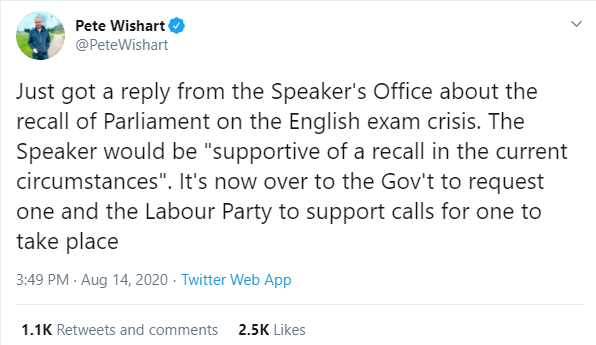

In a crisis the House of Commons is hamstrung if it is in recess, for MPs are not masters of their own House. While any MP can make representations to the government and the House of Commons Speaker to request a recall, under Standing Orders only a formal request from ministers to the Speaker can actually trigger one.

, Director

Dr Ruth Fox

Dr Ruth Fox

Director , Hansard Society

Ruth is responsible for the strategic direction and performance of the Society and leads its research programme. She has appeared before more than a dozen parliamentary select committees and inquiries, and regularly contributes to a wide range of current affairs programmes on radio and television, commentating on parliamentary process and political reform.

In 2012 she served as adviser to the independent Commission on Political and Democratic Reform in Gibraltar, and in 2013 as an independent member of the Northern Ireland Assembly’s Committee Review Group. Prior to joining the Society in 2008, she was head of research and communications for a Labour MP and Minister and ran his general election campaigns in 2001 and 2005 in a key marginal constituency.

In 2004 she worked for Senator John Kerry’s presidential campaign in the battleground state of Florida. In 1999-2001 she worked as a Client Manager and historical adviser at the Public Record Office (now the National Archives), after being awarded a PhD in political history (on the electoral strategy and philosophy of the Liberal Party 1970-1983) from the University of Leeds, where she also taught Modern European History and Contemporary International Politics.

Get our latest research, insights and events delivered to your inbox

Share this and support our work

The rules governing recall are set out in House of Commons Standing Order No. 13. The Speaker of the House of Commons is only required and able to consider whether the House should be recalled on the basis of representations made by ministers that “the public interest requires that the House should meet at a time earlier than that to which the House stands adjourned”. If ministers make such representations, then the Speaker is required to consider whether the public interest does require recall. If s/he agrees that it does, then s/he must appoint a time for the House to meet.

The current Standing Order dates back to 1947, although the government has had the power to recall Parliament during an adjournment since the Meeting of Parliament Act 1799. Between 1920 and 1931 the power to recall the House rested with the Speaker after consulting with the government; between 1932 and 1947 the power assumed its present form, of the Speaker recalling the House but only at the government’s request. This position was then formally reflected in the wording of the Standing Order adopted in 1947.

The current provisions have long been regarded as an inadequate basis for recall. They demonstrate the excessive level of control that the government exercises over the operation of the House of Commons. The House ought to be able to convene itself without having to obtain the permission of the government.

In 2001 the Hansard Society’s Commission on Parliamentary Scrutiny argued that if Parliament was to be an effective forum at times of crisis, and retain its significance to public debate, then the rules governing recall had to be revised. The Commission suggested that the Speaker be granted the power to recall Parliament at times of emergency if one or more MPs requested it and following consultation with the party leaders.

In his October 2017 Hansard Society Lecture, then-Commons Speaker John Bercow MP (then also the Society’s Co-President) also called for reform of the recall procedure, arguing that the House belongs to all its Members, not just the minority who occupy ministerial office. In doing so, however, he acknowledged the need to build safeguards into any new procedure, to ensure that the recall process was not open to partisan exploitation and was used only in genuinely urgent circumstances. He suggested, for example, that a petition for recall might be launched “if it involved a relatively high number of our 650 MPs, perhaps a quarter of them, provided that at least a quarter of that quarter were drawn from those who support the Government and at least a quarter from the Opposition.” Such a model would set a relatively high threshold for recall, have the advantage of requiring political balance, and protect the Speaker from being put in an awkward decision-making situation.

To date, however, little progress has been made in reforming the recall rules.

In 2003 the House of Commons Procedure Committee largely agreed with the proposal of the Hansard Society Commission and recommended that the decision on recall should rest with the Speaker.

In 2007, in its The Governance of Britain Green Paper, the then-Labour government proposed that “where a majority of members of Parliament request a recall, the Speaker should consider the request, including in cases where the Government itself has not sought a recall. It would remain at the Speaker’s discretion to decide whether or not the House of Commons should be recalled based on his or her judgement or whether the public interest requires it, and to determine the date of the recall.” However, these proposals were never implemented.

In October 2007 the House of Commons Modernisation Committee also initiated an inquiry into Dissolution and Recall (to which the Hansard Society submitted evidence), but it did not complete its deliberations before the Committee ceased to meet.

Although the 2003 and 2007 select committee inquiries did not make progress, they helpfully set out some of the procedural details that would need to be ironed out in any reform process. For example:

How will applications for recall be made and how will these be authenticated?

If a threshold is applied but an application for recall does not immediately have the requisite number of supporters, how long should the application remain ‘live’ in order to try to gain the necessary signatories?

How will multiple similar applications for recall be aggregated?

If a successful application for recall does not come from the government, in whose name should the motion on the Order Paper on the day of recall stand? (Current Standing Orders provide only for government business on the day of any recall, with the government tabling the necessary motion for discussion.)

If the recall is secured by a non-government MP, then should it be possible for any government business to be transacted on that sitting day, or should the business be restricted to discussion of the recall-related motion only?

In the House of Lords the Lord Speaker can recall the House after consultation with the government. The House of Lords Companion to the Standing Orders explains that the “Lord Speaker, or, in his absence, the Senior Deputy Speaker, may, after consultation with the government, recall the House whenever it stands adjourned, if satisfied that the public interest requires it or in pursuance of section 28(3) of the Civil Contingencies Act 2004.”

In Scotland, responsibility for recalling the Parliament also rests solely with the Presiding Officer who “may convene the Parliament on other dates or at other times in an emergency” (Standing Order Rule 2.2.10). In practice, the parties are consulted through the Parliamentary Bureau – the body that organises the business of the Parliament and which is chaired by the Presiding Officer.

In Wales, in normal times the Parliament’s recall arrangements are similar to those of the House of Commons. Standing Order 12.3 provides that the Presiding Officer may recall the Senedd to consider a matter of “urgent public importance” at the request of the First Minister. However, during the pandemic, temporary changes have been made to the Standing Orders, and the Presiding Officer may now recall the Senedd with the agreement of the Parliament’s Business Committee “to consider a matter of urgent public importance related to public health matters” (temporary Standing Order 34.9).

In Northern Ireland, the Assembly has been recalled on Tuesday 18 August 2020 to consider the situation concerning the grading of GCSE and A-level examinations. In Belfast, under Standing Order No. 11, recall must be initiated for the purpose of discussing one or more matters of urgent public importance if notice is given to the Speaker by (a) the First Minister and Deputy First Minister, or (b) by not less than 30 Members.

Without the government initiating reform, there are still at least two possible routes to take the reform of recall forward in this Parliament.

First, the House of Commons Procedure Committee could revisit the matter and conduct its own inquiry. This would enable the issues to be revisited and the views of newer MPs to be taken into account. However, while the Committee can make recommendations, it cannot implement them; it would still be reliant on government to do so.

Alternatively, consideration of recall arrangements could form part of a wider review of Standing Orders which the Leader of the House of Commons, Jacob Rees Mogg, suggested when he gave evidence to the Procedure Committee in June that the Committee could helpfully undertake. The Hansard Society suggested in October 2019 that such a review might be a priority for the new Speaker of the House via a new Rules Review Committee. Alternatively, such a Rules Review Committee could be established as a sub-committee of the Procedure Committee. A fresh review of Standing Orders which sought to address the question of ‘Whose House is it?’ might help to move the debate about recall forward.

More

Related

Blog / Back to the future? House of Commons scrutiny of EU affairs after Lord Frost's exit

The recent rearrangement of responsibilities for the government’s handling of EU-related affairs raises questions about future parliamentary scrutiny of these issues. In some respects pre-2016 institutional arrangements are restored, but the post-Brexit landscape presents new scrutiny challenges which thus far MPs have not confronted.

Blog / "Will they come when you do call for them?": Should select committees have real power to compel evidence?

In a recent report the House of Commons Privileges Committee recommended the creation of a new criminal offence to deal with the rare problem of recalcitrant select committee witnesses. The proposal is narrow and looks workable. However, it remains controversial, and the Committee has invited further views, with final proposals expected later in 2021.

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Budget

In order to raise income, the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its taxation plans. The Budget process is the means by which the House of Commons considers the government’s plans to impose 'charges on the people' and its assessment of the wider state of the economy.

Briefings / Who chooses the scrutineer? Why MPs should resist the government's attempt to determine the Liaison Committee chair

Should the Liaison Committee have as its chair someone who is not simultaneously a select committee chair, and should the identity of that person be determined by the government? The answer to these questions will tell us much about how this cohort of MPs, particularly government backbenchers, view the relationship between Parliament and the executive.

Blog / "... as if the Commissioners had walked into Parliament with a blank sheet of paper": Parliament's procedural handling of the Supreme Court's nullification of prorogation

The Supreme Court's 24 September nullification of the prorogation that had at that point been underway presented Parliament with a procedural and record-keeping problem. Here, the Clerks of the Journals in the two Houses explain how it was resolved.

Blog / The 2019 Liaison Committee report on the Commons select committee system: broadening the church, integrating with the Chamber

In its recent landmark report, the House of Commons Liaison Committee recommended a widening of the circle of those that select committees should hold to account, and a turn towards the public in all committee activity, but also tighter links between select committees and the House of Commons Chamber.

Blog / The Independent Group of MPs: will they have disproportionate influence in the House of Commons?

The roles occupied by members of The Independent Group - particularly on select committees, where they retain a number of important posts and command two and a half times as many seats as the Liberal Democrats – could give them more influence than their small, non-party status might normally be expected to accord them.

Blog / The DCMS Committee, Facebook and parliamentary powers and privilege

For its 'fake news' inquiry the House of Commons DCMS Committee has reportedly acquired papers related to a US court case involving Facebook. Andrew Kennon, former Commons Clerk of Committees, says the incident shows how the House's powers to obtain evidence do work, but that it might also weaken the case for Parliament's necessary powers in the long term.

Publications / Opening up the Usual Channels: next steps for reform of the House of Commons

In a speech to the Hansard Society on 11 October 2017, of which the full text and audio recording are below, the House of Commons Speaker, the Rt Hon John Bercow MP, proposed three key reforms for the House: a House Business Committee; reforms to procedures for Private Members' Bills; and a loosening of the government's exclusive control over recalling the House.

Blog / Corbyn's 'Save Our Steel' e-petition shows why the rules governing the recall of Parliament need to change

In a time of crisis Parliament is hamstrung if it is in recess. MPs are not masters of their own House because, in accordance with House of Commons Standing Order 13, only government ministers - in reality the Prime Minister - can request a recall of Parliament.

Latest

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Budget

In order to raise income, the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its taxation plans. The Budget process is the means by which the House of Commons considers the government’s plans to impose 'charges on the people' and its assessment of the wider state of the economy.

Guides / Financial Scrutiny: the Estimates Cycle

In order to incur expenditure the government needs to obtain approval from Parliament for its departmental spending plans. The annual Estimates cycle is the means by which the House of Commons controls the government’s plans for the spending of money raised through taxation.

Data / Coronavirus Statutory Instruments Dashboard

The national effort to tackle the Coronavirus health emergency has resulted in UK ministers being granted some of the broadest legislative powers ever seen in peacetime. This Dashboard highlights key facts and figures about the Statutory Instruments (SIs) being produced using these powers in the Coronavirus Act 2020 and other Acts of Parliament.

Briefings / The Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Bill: four delegated powers that should be amended to improve future accountability to Parliament

The Bill seeks to crack down on ‘dirty money’ and corrupt elites in the UK and is being expedited through Parliament following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This briefing identifies four delegated powers in the Bill that should be amended to ensure future accountability to Parliament.

Articles / Brexit and Beyond: Delegated Legislation

The end of the transition period is likely to expose even more fully the scope of the policy-making that the government can carry out via Statutory Instruments, as it uses its new powers to develop post-Brexit law. However, there are few signs yet of a wish to reform delegated legislation scrutiny, on the part of government or the necessary coalition of MPs.